|

Note: What follows is adapted from a paper submitted as part of my education under the Antioch School. The requirement for the paper was that I design "a set of guidelines for establishing local churches anywhere according to an advanced biblical understanding of Paul’s concept of establishing local churches, including instructions for 'house order' of local churches."

If our work is to be establishing churches, then we need to know how to establish churches in a way that is flexible enough to fit into contexts as widely different as first-century Jerusalem and modern New York, rigid enough to do the work Christ has intended for the church without straying from His intended model, and drawn from scripture as the normative expectations Christ and the apostles had for the church. The process we see Paul implement time and again essentially falls into three stages: assemble a body, impart solid teaching, and entrust to established leaders. This article will explore a definition and the necessary elements of each step.

We see more of this work in Acts than in Paul’s letters, largely because Paul was often writing letters to bodies he’d already assembled. There is limited exception to this, in that Paul occasionally gives instructions to his recipients on how to identify people who should not be in the body and thereby performs work related to, but not actually within, the assembly stage. Throughout Acts, however, we see the initial practice in more detail. Jesus assembles His followers and gives them instruction to wait as a body for the work He has for them to commence.(1) In response to Peter’s sermon at Pentecost, those who believe are baptized into the body and begin sharing their lives with one another. Paul consistently goes to a gathering place (usually a synagogue), delivers the gospel message, and then sets apart those who believe into a new body.

Even when we see individuals become Christians, they do so in community. Cornelius and the Philippian jailer are both saved alongside their households, Apollos is familiar enough to the church of Ephesus after his conversion that they were willing to send a letter vouching for him when he traveled to Corinth in the very next verse. We tend to focus on Paul’s miraculous encounter with Jesus on the road to Damascus, but his conversion was not complete at that point; the Holy Spirit doesn’t descend on Paul, a repeated sign for the moment of true conversion in Acts, until Ananias comes to welcome Paul into the church body. There is, in fact, only one exception in all of Acts: the Ethiopian eunuch is not immediately brought into a local church body when he is baptized by Philip. Church history tells us that he brought the gospel back to his own country and a community of faith was immediately formed there, but we have no record of this in scripture. The oddity of this event is, itself, indicative of how the alternative is the accepted norm throughout scripture. I am of the belief that every valid(2) denomination and theological movement within Christianity is really good at highlighting at least one, but not more than a small handful, of truly important elements of the faith that other denominations or theological movements overlook or undervalue, and that we would benefit greatly by more deeply considering these pockets of truth we can learn best from outside our own traditions. Sometimes they become so absorbed by this truth that they let something else wither entirely or develop a wrong understanding of a related concept out of misplaced focus, but the foundation they are using for this is still worth understanding. This is one area that I would argue the Roman Catholic Church has us at a theological disadvantage: there really is no salvation outside of the church. The See has, in some times and in some ways, taken this to a questionable place, but the proper solution cannot be the rugged individualistic salvation we have accepted so long in Baptistic, Pentecostal, and other related environments. We are not, I would argue, saved as individuals; rather, we the church are saved together.(3) Upon adoption as children of God, we are brought into communion with the rest of His children. We are members of the body, indeed, we cannot be outside of the body of Christ without being apart from Christ. Salvation inherently gives us a body to which we belong, and our growth must happen within the context of that body. There are few places where this is more apparent than in a church plant. I have been a member of four church planting teams, one of which I led, and these have produced some of my closest relationships to date. The scope of the work, when faced with a small band of Christians, pushes people in a distinct way. I have heard much about how church planting work tests one’s faith and missional focus, quickly weeding out anyone not prepared for the work and any aspects of our lives that interfere with the work, and this is all true; but I have heard significantly less about how it connects the people involved. My wife and I have grown considerably in our relationship through the ups and downs of church planting. When we were working in Greenfield with one other couple, we became family. Our kids were constantly together and began to act like siblings, the mother of that family is still my wife’s best friend; a divorce and seven years later, and we make a trip to New Jersey every year to see her and her husband and the kids even when we don’t have the means to visit my biological family the next state over. We all grew together, we invested in one another, we hurt for one another, we rejoiced together, and although no lasting church was established in Greenfield from that work, I believe we have displayed the kingdom of God more accurately alongside them than we have in many churches with longstanding buildings and budgets. We have another family with a similar level of connection, and that grew out of working together on a church planting team in Fitchburg. The mistake we make too often is conflating the importance of unity with the styles we use in our gatherings. We are commanded not to forsake the assembly; we are nowhere commanded to sit facing a stage and listen to a half hour lecture. I don’t have much against our modern practice of gathered worship—other than the strict rigidity with which we practice it—but this structure is not essential and is, at times, detrimental to that which is essential. That is, getting everyone together at a specific time on Sunday morning, singing a set constant number of songs, praying at scheduled intervals, listening to a sermon, and receiving a benediction is not a bad model in and of itself, but our insistence on it as “what church looks like” diverts our attention from how the church is actually intended to function. It’s easy to view our unity as defined by how many of us are sitting in the same room at the same time hearing the same message, but that isn’t where the unity of the body is practiced, and having the room become too large makes it impossible to practice any real unity. The body, in order to look like the church as established by Christ, must be grounded on intimate relationship guided by solid teaching under the authority of established leaders. The guidelines for proper assembly, then, are that the body is gathered in an environment that facilitates and encourages intimate relationships, the body invests in the spiritual growth and practice of spiritual gifts by all members, the body puts structure as secondary to purpose, and the body is prepared to send out members to establish a new assembly before it grows too large to accomplish the previous guidelines. There are a few concrete ideas that arise from this—such as the need to have some offline connections and relationships and gatherings, the need to guide spiritual formation in the proper way of Christ, and the need to send out church plants rather than growing too large for deep community—but much of the practice of this will be contextual and must be flexible to be applied correctly in different environments and with different people. If the purpose of the church involves the healthy growth of Christ’s body, both by multiplication and by maturity, as this blog has argued it does, then the structures that accomplish that purpose must be curated to the place and time and people to which it ministers.(4) These guidelines direct the boundaries of that flexibility, but must remain broad.

The assembled body must be built upon and maintained by the truth of who Christ is and to what He has called us. The way we ensure this is through deep, consistent, and accurate teaching, delivered by some number of established leaders who are faithful to the truth of scripture. This teaching is broadly concerned with a right understanding of God, a right understanding of our relationship to God, and a right understanding of our relationships among ourselves.

A right understanding of God is the basis of all theology, and is concerned with the nature and works of God in all matters. Every other teaching flows from this; everything about the church is defined by who God is and what He has done and is actively doing and will yet do. Here is covered such topics as the nature of the Trinity,(5) the person of Christ, the work of salvation, and God’s ultimate victory at the end of the age. This topic is vast, and must be constantly revisited and expanded upon in order that its application in the other topics is held to the standard of truth. A right understanding of our relationship to God is focused on who God is to us and who we are to Him. This topic tells us about our need for salvation, how our salvation has changed our standing before God, and how we are to grow in the new life to which God has called us. Here we see how submission to God is imaged in our submission to church leadership and the submission of wives to husbands and children to parents, how the mission of Christ has been handed to the church and therefore what goals the church must seek to achieve, and what it means to become children of God and heirs of His promise, among others. This teaching must be delivered frequently to ensure the church is aligned with its role in God’s plan, but it must also be a source of guidance for all the church does as a body and how the church invests in individuals. The first topic tells us what God we serve; this topic tells us how we, as a body, best serve Him, and must be always on our mind and in our teaching to ensure we approach our mission properly.

A right understanding of our relationships among ourselves guides our understanding of life within the family of God. This topic is about how we engage with one another, what authority and submission look like in daily practice, and how to live out the love that Christ has poured out so lavishly on us. Here we get into the nuts and bolts of the house order, describing the terms of our submission to authority within the church and within the home, detailing the practice of the nested dualities I covered in a previous post, applying the calls in scripture to view others above ourselves and love our neighbors as ourselves. This teaching is almost always an application of one of the other topics, but is important and must be included whenever application is being delivered. Our assembled body must be guided on how to be an assembled body, and this topic concerns itself with that more than any other.

When I was planting in Greenfield, I mapped out a sermon series that lasted one year as our very first study. Essentially, it worked through the Old Testament and sought to understand its themes through the lens of Christ, beginning with creation and ending, at the beginning of Advent, with Christ as the culmination of all the other things we’d discussed. The aim of this study was multifaceted; it revealed how the work of God and the heart of Christ was present throughout all scripture, it focused our attention on Christ in all matters, and it trained us to see Christ as the focus of every story and every theme throughout the Old Testament. The idea was that new people coming into the church would learn who God is through His dealings with mankind, and established Christians would be reminded of the role of Christ in redemptive history and the application of the Bible’s lessons. That the church would begin rooted in this understanding and what it means for us. I was not able to finish the series before the church folded, but have kept the basic outline just in case I have opportunity to explore it again. Because this is the nature of the guidelines for imparting solid teaching; that established leaders point to God through His word to reveal His nature, call the body to live in light of our role in His purposes, and guide the body to daily lives reflecting the truth and glory of God among us. That teaching plan I started to put into practice was aimed at these very objectives, but obviously it is not the only way to apply these guidelines. The objective is simple: teach often, teach faithfully, and apply the teaching to every aspect of the life of the church and the lives of its members.

Paul, having bound a body together and delivered the word of God faithfully to them, identified those who were gifted and growing in maturity in such a way that they could be trusted to continue the work after he was gone. These were drawn from the body itself and placed into the role of leadership, held to a higher standard to ensure they were fit for the duty, and taught the functions of a leader to properly guide the body. These people were expected to teach faithfully, to protect the body from false teaching, to maintain the house order of the church body, to carry out the work of church discipline, to identify and train new leaders, and to send out parts of the body to establish new bodies as appropriate.

Paul details the means for selecting these leaders in his letters to Timothy and Titus, but their work is constantly visible in all his letters. The leaders were the ones expected to impart the teaching Paul was including in his letters, they were the ones being called to oversee any acts of discipline Paul called for, and they were responsible for the daily application of the principles Paul explained. Peter directly addressed his letters to the leaders themselves because of these responsibilities. In the house order, the leaders were those who held the honor of leading and directing the church, and the responsibility to do so in a manner that glorifies God and serves His purposes. The leaders are those who impart the teaching, who guard the body, who constantly refocus the body on Christ to ensure He is the foundation of the body’s work and unity. The guidelines, then, are that the church has leaders in place who have been properly identified by an established church body and trained in service to Christ, who maintain the standards of leadership described by Paul, who are treated as authoritative by the body, who are able to teach and willing to correct, and who are able and willing to identify and train new leaders. These leaders should be placed within the biblical duality of elders and deacons, with the office of elder reserved for men. There must be a plurality of leadership; one man’s mistakes cannot be given enough power to damn the mission of the entire body.

The guidelines which must shape all churches in all places and times, then, are the broad ideas illustrated through these areas of concern. That the church must be an assembled body living in deep relationship that glorifies God, taught faithfully on the nature of God and the work He is doing in and through that body, under the authority of established leaders who center the body on the truth of God and guard it against distraction and alternative purposes. Establishing a church is the process of putting all these guidelines into place and fulfilling them, leading to the spiritual maturity of the body and its members. Our flexibility within them is necessary to engage with where God has us and who He has put into the body, and we should try to mold our systems to our context rather than being ruled by the systems we’ve inherited. But these guidelines are to be respected both as a direction to aim and as boundaries to what we cannot do; the body of Christ can no more tolerate a lack of leadership or the presence of bad leadership than our mortal bodies can tolerate cancer. We can bend within the principles described by Paul, but cannot break or try to escape them.

Footnotes

0 Comments

What follows was originally a paper written for my Church Administration class at Northeastern Baptist College in January 2019. It has been adapted into its present form. Churches have a number of functions, many of which are specifically local. It is within the local context that a church baptizes believers, interacts with its community, carries out discipleship, practices communion, participates in regular corporate worship, and invests in the lives of one another. If, however, we are to understand the church as being a vehicle for the Great Commission to carry the gospel of Christ to all the world, as Baptists hold, then there needs to be some means by which the local church functions on a global stage. Now, no local church body can carry out the fullness of its mission on a global scale--people from Malaysia simply will not attend a communion service in Iowa on a regular basis--so how is the global function of the local church related to the local function? Historically, the primary means by which the local church extends its mission to the global stage has been by sending out individuals who have a working partnership with the local church and operate in a different, frequently overseas, local context. A working partnership is more than simply sending money, however, and requires that the church actually participate in global work on a fairly regular basis. This is the basic purpose of short term mission trips: to participate in and support the work of the church outside of the immediate local context. Short term missions, however, are a fairly new phenomenon in American Christianity. Bob Garrett, then-professor of missions at Dallas Baptist University, wrote in 2008 that “In the 1960s and into the 1970s most denominational mission boards and missionary sending agencies were still sending out exclusively career personnel” and went on to explain that the rise of short term missions was not only unexpected, but actively opposed by some. As such, there is much about the practice of short term mission trips to be clarified and understood. Operating in this manner requires a great deal of planning, and the local church must have an understanding of what it is they are trying to do by sending short term mission trips and how best to accomplish those goals. This article is intended to give an overview of some of the primary concerns that arise in planning a trip, with a particular focus on the role of the church administrator in planning, organizing, and carrying out both a church policy of short term missions and individual trips a given church may send out.

The success of a church short term mission trip depends in large part on the work of the church administrator. The fact is that mission trips require far more planning than picking a location and getting to work. Even when traveling to assist an established long term missionary, there are a wide range of variables that have to be addressed and balanced to ensure that the trip has a clear goal that can be achieved and that the work is carried out well. In A Guide to Short Term Missions, H. Leon Greene notes that “Commonly, in the spring, thoughts turn toward a summer mission trip. This is not nearly enough time to complete your preparations.” Greene’s concern is that there is so much work involved in planning an effective trip that preparations should start far earlier; he states in the same paragraph that “ideally, a member of the team should visit the site a year before the team’s departure date.” Note that planning under this model does not begin a year before the trip. After all, the person who scouts out the site has to know what site they are going to in the first place. Planning has to begin early enough to have someone ready to visit the site a year before the trip. Over a year of planning and organizing cannot be done as the background noise of someone partially invested in the work. Such a task must be given over to someone who is committed to the operational side of the mission, who can think about long-term objectives, and who understands the facets of planning a successful trip. In a church large enough to have a dedicated church administrator, this would be part of their work, in conjunction with any missions coordinator the church may have. For any other church, however, someone needs to take on the responsibility of organizing the missions work of the church. A volunteer missions coordinator should be selected with a great deal of discretion; they are taking on a highly important role, and the church needs to know that they are committed to the work, sound in their theology and goals, and submitting to the pastor and the church.

Churches should have a missions policy. Having an established system can eliminate a host of issues that arise in mission planning. A good church mission policy should cover, at the very least, any location preferences the church may have (such as overseas, domestic, only places with missionaries the church supports, etc.), criteria for members of the trip which includes an acknowledgement that some people are called to personally participate in non-local mission and some simply are not, fundraising policies to cover the costs of trips (if not addressed elsewhere), and specific point people who are responsible for determining whether or not a given trip suggestion will be pursued by the church. Once this policy is in place it can guide much of the process that follows. Any trip that simply does not conform to what the church is able to support will be revealed quickly before resources, including time, are spent on it. The issue of calling is a major one, however. A recognition that there is an actual calling involved in cross-cultural mission ensures that the vetting process for personnel, especially trip leaders, is focused on working under God’s design instead of just filling a trip with an impressive number of people. Mission trips will not be as effective if they do not have at their core the understanding that God wants this set of people in this place to accomplish this work. A church policy for mission trips should aim to ensure that they are built to this standard.

There are a number of issues that need to be addressed before detailed planning on a trip can begin. The first really is simply determining where the trip will be and when. Nearly every resource available on planning a trip suggests going where there is an established long term missionary who has a relationship with the sending church. If a given church has existing relationships with multiple missionaries, one will have to be chosen to receive a team. Garrett notes, “Realities on the ground should play a key role in determining the specific work of the trip,” and one of the easiest ways to accomplish this is to ask a number of missionaries about their needs and work that they want support on which the missionary and their community can continue after the short term team has returned home. The reason it is advised to get trip ideas from long-term missionaries and to let them set the course of the work is that there is growing concern over how we do short term trips. The Catholic Church, for instance, published an article in 2015 in which the Mike Gable introduced his premise with the statement, “I am convinced mission offices, parishes, and schools across the United States need to stop funding and sending harmful, arrogant, and poorly trained short-term mission groups.” The reason for this blunt condemnation is what Gable refers to as a “‘heroic’ model of mission” that relies on the notion that Europeans and North Americans have “a sacrificial duty to ‘bring civilization and God’ to the so-called ‘pagans’ who supposedly needed Western culture to be fulfilled human beings.” This description of the actual effects of this mission style reverberates across denominational lines. Gable notes evidence that points to communities receiving teams agreeing to whatever idea the teams have, out of concern for offending their guests, even when the work is not beneficial to the community and may actually need to be undone as soon as the team leaves. In an interview, anthropologist Jeff Haanan argued, I am not for the narrative that has typically driven these trips: ‘We are going because there’s this tremendous need out there that we have to meet. And there’s this burden that we have as the wealthy country to go and do something in another place.’ I support transforming this narrative so that it becomes, ‘How can we connect with what God is doing in other parts of the world? How can we learn to be good partners with Christians already in these places? How can we participate in what the church is already doing in these countries in effective ways?The solution Gable points to is a relational one. Gable notes, “A recent study shows most U.S. mission groups prefer construction projects, while most host communities prefer building long-term relationships humbly walking together in Christ. Only after partnerships of trust and respect have matured should it be appropriate to discuss possible service and social justice projects together.” The fact is that we can talk a great deal about bringing the gospel into a new context, about learning the culture so as not to unnecessarily offend the people we minister to, about doing work that they need, but if we do not listen to them about what would be a blessing to them, none of that will matter. We must begin with a relationship, ideally through a long-term missionary or a native pastor, and respect their knowledge of the needs and gifts of the community rather than beginning with work we would like to do and then looking for someone we think can use it. If a number of missionaries have provided ideas for teams to address, the church administrator or individual responsible for planning trips should take time to examine each, alongside the actual resources of the church, to determine which ones are feasible. A church with no young people and a lack of construction-minded members will simply not be a great benefit to a community that needs houses built. A church with a poor congregation may have difficulty raising money to support an extended stay or a project that involves a large amount of supplies. During this stage, members of the church can be approached about prayerfully considering taking part in a trip. Those who are interested should be aided in establishing a network of supporters who will pray for the trip and the individuals from that point until the team has returned home. Looking at the gifts and calling of those who feel led to participate may be very helpful in narrowing down the options for where the team will go and what kind of work they will perform while there. Once the works that cannot be done by the sending church or do not fit the mission of the church have been ruled out, that which remains can be investigated further. Gathering more information on the exact details about what would be needed for each possible trip, examining the urgency of each idea, and pitching these ideas to potential team members and leaders may make one option stand out as the best fit for this body at this time. It may instead result in multiple trips being planned for different times. Once the church has decided upon a specific trip to plan at this time, the next phase can begin.

Earlier, Greene was cited as calling for someone to visit the site of the trip a year in advance. This is identified because quite a lot actually has to happen during that year. In Greene’s book, he described events where going early enabled a team leader to differentiate between two possible sites in the same community and determine which one was best for the planned work, and others where early treks to the community clarified difficult travel options and ensured that the team knew how to get where they were going and how long it would take to get there. The person visiting early can take note of what supplies the team may need and their availability, as well as any local wildlife or plants that people in the team may need to be ready to encounter. It is not that those who live there cannot be trusted to know their own environment, but that someone who lives with certain conditions and handles them regularly may not think them notable enough to mention to a visitor. Everyone in my family has hit at least one deer with a car in their life, with one exception, but I have never warned someone going to my home area from Massachusetts to watch for deer on the road. It did not register to me that there are fewer deer here, and people are not as accustomed to watching for them, until people began responding with surprise to my stories about being in cars that hit deer. Having someone who comes from the same context as the church group check out the site will bring up things that people from that context need to know about the one they are entering. An early trip also initiates an ongoing conversation between the team leader and anyone already on the ground, which helps deepen the relationship between the team and the community and provide updates on changing situations in the community. That year gives the team members, who have already been building a team of people to pray for them, time to begin raising any necessary funds. It gives them time to get passports if needed, to request time off work, to make arrangements to be dropped off and picked up at the location where the team will meet for their journey. It gives the church time to arrange transportation, buy tickets, and secure housing at lower costs. According to Forbes, the best time to buy plane tickets, for example, varies by season but usually falls into the window of two to three months in advance. Having solid plans nine to ten months before buying plane tickets gives the church ample time to know exactly who needs those tickets. During this year, if the team is traveling out of the country, it is also important to have team members visit their doctors and make any necessary arrangements for vaccinations, prescriptions, or other medical concerns specific to the location. If the team will be arriving in the summer and the scout visited the summer before, they can give the team detailed information about some of the concerns they noticed thriving at that time, such as mosquito populations or water conditions. This needs to be a year of prayer, of active work in planning details, and of getting the church excited for the mission. The church is sending this team--the church needs to be on board with what the team is doing. Taking the time during that year to introduce the community, the need, and the vision for this specific trip ensures that the church has time to think over what is being planned and get excited to participate in it. It gives people who would be interested but had not previously expressed interest the chance to get involved. It also provides an opportunity to raise money from the church itself. In discussing fundraising in general, Dave Wilkinson noted that donors need ...the chance to give realistically and prayerfully. This includes advance notice before the offering is received. It means hearing how this special offering fits into the giving scheme of the whole year and what other special offerings are anticipated. For contributors, pacing is important, as is knowing what ministries they will have opportunity to support, so they can give to those closest to their hearts.One other issue that needs to be addressed during this year is training. The team needs the opportunity to learn what will be expected of them during the trip, how to do the work, and how to interact with the culture. They will have a short amount of time to make an impact while on site, and cannot spend all of it figuring out how to start the work. The relationship with someone on site helps immensely here, as they can focus these efforts on specific conditions relevant to the site.

There should be no more questions or foreseeable issues to handle a few weeks before the trip. Surprises will arise, as they always do, during the final weeks of preparation and the trip itself; but a well-planned trip should minimize these as much as possible by having details mapped out, team members trained, and supplies gathered or on site. By this point, the team should be able to focus entirely on prayer, personal down time, building relationships, and doing what they are being sent to do. The church and any others that have been supporting the work should be encouraged to continue praying for the success of the trip and the glory of God revealed to everyone involved. While on site, the team should operate under the guidance of the team leader who is working alongside, or even under, the team’s primary contact in the community. When the team returns, they should be invited to tell the story of what happened to the gathered church and other supporters. One important thing to keep in mind after a trip is that the relationship does not end when the plane lands. The team should be encouraged to continue contact with anyone they built relationship with while on site, the church should continue to cultivate a relationship with long-term missionaries and/or native pastors in the community, and that community should hold a standing option as somewhere that future teams can visit. Part of building relationships is not abandoning those relationships as soon as the immediate work is over. If short term mission trips are going to aid in the mission of the church to reach a global stage, they must open the door for the church to continue thinking and operating on a global level. As Haanan noted, “the whole trip should be an experience of learning, growing, and serving God. Listening and learning from people, about people, about places, about what God is doing--this is God's mission, and it should be ours as well.” Everything that happens before, during, and after the trip should serve this broader purpose and bring it home to the sending church.

A Survey of Causes and Consequences, with Particular Focus on the Role of Baptists ThroughoutNote: The following is adapted from a paper originally written for my Baptist History and Distinctives class in May, 2018. The assignment was to explore an event from Baptist history, and out of curiosity, I decided to see if there was any in Ireland. This paper ended up being pretty important to me, as the process of researching it played a role in my wife and I feeling called to work in Ireland. That story will come in another post. On an island housing nearly 6.6 million souls, the Association of Baptist Churches in Ireland can only claim 117 churches with “over 8,500 members and represent a Baptist community of over 20,000”[1]. At barely 3% of the total population, Baptists can be overlooked in Irish life. Baptists have never held a position of great influence on the affairs of Ireland; baptist growth on the island has been incredibly stop-and-go, historically struggling against the established Roman Catholic Church in the south, the Presbyterian churches in the north, and the Brethren movement everywhere. In modern days, the rise of secularism has been both a hindrance and a blessing, as the non-religious mindset has become another hurdle to Baptist work but strides made in the face of it have been profound. If Irish Baptists are readily ignored in Ireland, they are even more so for those outside of the island. Few books of Baptist history discuss Ireland, and those that do generally give it very little space. In its treatment of Greater Britain, H. C. Vedder’s Short History of the Baptists gives one paragraph to Ireland and two to Alexander Carson, a prominent leader in Irish Baptist life. In summarizing the paragraph on Ireland, Vedder simply states that “comment is almost needless. Baptist churches have ever found Ireland an uncongenial soil”[2]. This is hardly surprising, given the nature of their arrival to the island. In fact, the two most influential events in Irish Baptist history are arguably the conquest by Oliver Cromwell’s army and the Ulster Revival of 1859, and Baptists themselves, while reasonably associated with both, played very little public role in either. The concern of this post will be the latter, but it cannot be fully divorced from the former. The context of the Ulster Revival can be traced through three sources: the general tone of Baptist life in Ireland as established by Baptist arrival and initial struggles, the Prayer Meeting Revival in America of 1857-1858, and the immediate environment in which the Ulster Revival occurred. With this understanding in place, consideration can be given to the revival itself and its results, which are still felt today. Early Irish Baptists

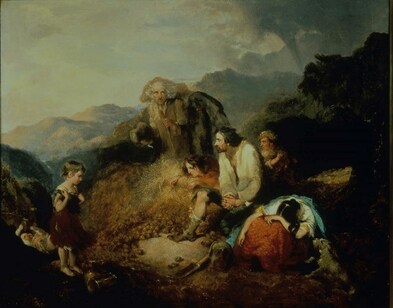

presented as a religious crusade by claiming that the Catholic population there had driven Protestants out of St Peter’s cathedral to hold Mass; Catholic priests in particular were targeted by the soldiers [5]. Ultimately, 3,000 are estimated to have died at Cromwell’s hand in Drogheda. Later massacres and general disregard for the Irish set a dark view of the man and his army by the native Irish. Owen did not remain in Ireland, but “when [he] returned from Ireland, pleading for missionaries to be sent to the island, Patient was chosen by Parliament as one of six ministers to be sent to Dublin” [6]. Thomas Patient had already served under William Kiffen in London and signed the London Confession of 1644. Patient helped form the Irish Baptist church in Waterford, one of very few from that period still operating today, before being given the preaching position at Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin. While there, “he was responsible for erecting the first Baptist Meeting House in Ireland, in Swift’s Alley, Dublin” [7]. This is the church Vedder refers to as beginning in 1653. The Baptists in Ireland had been strongly associated with Cromwell’s army, and Baptist churches on the island were still largely composed of soldiers and their families. When Charles II restored the throne in 1660, much of that army returned to England, leaving their churches largely empty. The remaining Baptists were caught in a vice between the crown and the Irish, both hating them for affiliation with Cromwell. In fact, “the Baptist cause is described as having ‘lingered rather than lived’” through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries [8]. A Revival of PrayerIn America, however, conditions were positive for Baptists and the general population right up until 1857. The first half of the nineteenth century in the United States was “characterized by tremendous economic growth and prosperity in the United States. There was a population boom and many people were becoming wealthy. The focus of many was on this world and as a result there was a deep decline in spiritual life” [9]. Those who grew wealthy began to leave the city centers, and many churches that had historically catered to the moving elite left the city with them. Those that remained took a keen interest in evangelism of the poor, especially in the wake of economic crash in 1857.  Invitation to Prayer Bench, statue of Jeremiah Lanphier in NYC, by Kristina D.C. Hoeppner. Some rights reserved, used under Creative Commons. To that end, North Dutch Reformed Church in New York City “employed a 48-year old businessman, Jeremiah Lanphier, as missionary to the inner city” [10]. Lanphier tried an assortment of outreach activities with limited success. He prayed regularly, asking God for some direction he should take to see the gospel take root among the people in the city. The direction that came to him was a weekly prayer meeting, one hour in length, in which people from the city could come or go as needed and pray, worship, and tell of the work God was doing. On September 23, 1857, “our missionary sat out the first half of the first noonday prayer-meeting alone, or rather he prayed, through the first half hour alone” [11]. He was then joined by five men, including a Presbyterian, a Baptist, and a Congregationalist [12]. A week later, twenty attended the prayer meeting, and attendance was nearing forty when the third meeting came together on October 7. With excitement building, it was decided that the meetings would occur every day, beginning immediately. As the building began to fill, other nearby churches and open spaces opened their doors for the growing prayer meeting movement. As of February 1858, “not less than one hundred and fifty meetings for prayer in this city and Brooklyn were held daily,” and that same month saw the first related prayer meetings begin in Philadelphia [13]. Almost immediately after, other meetings sprang up in cities as far abroad as Boston, New Orleans, St. Louis, and Chicago. Accounts began to arise about boats travelling to New York being swept up in the activity before making land. In Samuel Prime’s 1859 account of the prayer meetings, an entire chapter is devoted to the work done through Mariner’s Church in Manhattan to minister to sailors that carried word of their conversion overseas, and “ from there it spread to Canada, the British Isles, Scandinavia, parts of modern Germany, Geneva and other parts of Europe, as well as settler communities in Australia, southern Africa and India” [14]. An Island in Crisis An Irish Peasant Family Discovering the Blight of their Store by Daniel MacDonald, c. 1847, via Wikimedia Commons. An Irish Peasant Family Discovering the Blight of their Store by Daniel MacDonald, c. 1847, via Wikimedia Commons. When word arrived of God’s work through these prayer meetings, Ireland was eager for good news. The century had begun in a promising manner for Protestants, with Baptist churches, for instance, “founded at the rate of almost one per year” [15]. Baptists had turned their image around in Ireland thanks largely to their schools, which provided a solid education for both Baptists and non-Baptists. On considering the changing mindset of Ireland, Andrew Fuller wrote on behalf of the Irish Baptist Society that “the universal thirst for the acquisition of knowledge, are unquestionably in a great degree owing to the efforts of this and kindred societies, especially in the educational department, during the last thirty years” [16]. This work was greatly reduced, and eventually rendered nearly obsolete, after Ireland introduced public schools in 1831. New troubles, and opportunities for outreach, arose through famine. The Baptists in Ireland fared little better, if at all, than the Catholic majority during the potato blight that struck in 1842. The population was devastated, to the point that The combined effect of disease and emigration was a sudden and catastrophic fall in population: in 1841 it had stood at 8,175,000 and the natural increase might have been expected to raise it to about 8,500,000 by 1851; in fact, the census of that year showed a population of 6,552,000. And the famine not only halted the process of growth, but completely reversed it: the decline continued steadily, and by the beginning of the twentieth century the population of Ireland was only about half of what it had been on the eve of the famine [17]. Baptist churches, which were still few, were estimated to have lost “more than 3,000 both through death and emigration. As a result quite a number of churches disappeared in the south and west of Ireland” [18]. The Baptist churches of Ireland worked hard to provide for the needs of their neighbors, but between their own suffering and the loss of large numbers of adherents, they were quickly falling into a deficit. As the blight ended, more troubles struck Ireland, these coming in the form of higher taxes owed to Britain. William Ewart Gladstone, then chancellor of the exchequer in England, explained a new fiscal policy for Ireland in 1853 that included a higher spirit duty and an income tax that was expected to be temporary and only affect the wealthy. Instead, “the net result was that Irish taxation rose by some £2,000,000 a year, at a time when the only hope for the national economy was the investment of more private capital” [19]. Everyone in Ireland suffered to some degree under the plan. Meanwhile, Ulster was in a war over the political influence of religion. The Roman Catholic Church was dealing with an internal struggle over the concept of ultramontanism, a strong system of belief in the power of the Catholic hierarchy. Ultimately, the ultramontanists would win that battle with acceptance of the doctrine of papal infallibility in 1870. The ultramontanist movement was gaining strength in Catholic Ireland and the Presbyterians, fearful of losing political power to the Roman pontiff, “were appalled by government concessions to popery and in 1854 the General Assembly formed a Committee on Popery to monitor the progress of Catholicism in public life and arrange lectures on anti-Catholic themes” [20]. The Presbyterians themselves were recovering from an internal battle, where An Evangelical party had been making progress since the turn of the century in the largest Presbyterian grouping, the Synod of Ulster, and, during the second half of the 1820s, Henry Cooke had led this group in a campaign to expel a number of Arian ministers from the Synod. As a consequence of Cooke’s eventual triumph in 1829, Presbyterianism underwent a comprehensive process of religious reform that sharpened denominational identity and self-confidence, creating an Evangelical ascendancy within the denomination for the rest of the century [21]. This identity heavily incorporated Millennial hopes which saw the Papal See as the Antichrist which must be crushed before the glorious reign of Christ, and looked backward to the Six Mile River Revival of 1625-1630. They tied this revival and the rise of Presbyterianism to the newly-forming nationalistic identity of the Ulster-Scots, and eagerly sought to witness another movement like it that would stand against the growing power of the Catholic Church. The new movement the Presbyterians hoped for would be sober and respectable. It would produce great fruit with little fuss. What they saw happening in America in 1858 sounded like an answer to their very specific prayer; however, “revivals seldom conform to the sober desires of religious professionals. The revival of 1859 was no different and unleashed forces that challenged the status quo and caused considerable unease and controversy” [22]. The Ulster Revival of 1859In 1856, a woman named Mrs. Colville was sent by the English Baptist Missionary Society to spread the gospel in Ulster, especially Antrim. In that capacity, she encountered a young man named James McQuilkin, who she was able to lead to Christ. This event was “followed a few months later by three of his friends, Robert Carlisle, John Wallace and Jeremiah Meneely,” and the four of them found themselves ultimately under the care of the Reverend J. H. Moore [23]. Moore presided over the church in Connor, “a large Presbyterian congregation of over 1000 families” [24]. The following year, Moore took the four young men aside and urged them “to ‘do something more for God.’ He said: ‘could you not gather six of your careless neighbors, either parents of children, to your house or some convenient place on the Sabbath and spend an hour with them, reading and searching the Word of God?’ From this came the Sabbath School at Tannybrake (near Connor) and then a prayer meeting in an old schoolhouse near Kells” [25]. Conversions began to occur at Tannybrake and Kells, and one soul saved was a man named Samuel Campbell. Campbell returned home to Ahoghill, where he led his mother and siblings to the Lord. The last of his family to follow Campbell to faith was his brother, who in March 1859 was so stricken with the weight of his sin that he nearly collapsed upon hearing the gospel, and spent many days in dire spirits until he finally came to Christ. This would be considered the first of many manifestations that would accompany the revival that was beginning. As conversions were starting to draw attention in Connor and Ahoghill, word reached Ireland of the work happening in America. Inspired by the Prayer Meeting Revival, R. H. Carson, son of Alexander Carson and pastor of Tobermore Baptist church, decided on “the formation of a prayer meeting on a Friday evening and this proved to be a fruitful meeting, as a fortnight after its commencement, there were conversions. From March 1859 to March 1860, ninety-two souls were added to the church” [26]. This merged with the revival sparked in Connor as, by this time, “the Heavenly Fire was leaping in all directions through Antrim, Down, Derry, Tyrone, and indeed throughout all Ulster. From Ahoghill the revival spread until, in May 1859, it began to manifest itself in Ballymena” [27].  Coleraine, one of the major centers of the Ulster Revival, c. 1890. National Library of Ireland. The Presbyterians had also heard of the Prayer Meeting Revival, and had “dispatched William Gibson and William McClure as a delegation to North America. Gibson published in March 1859 a report of his personal experiences in the previous autumn as an introduction to an account of the revival in Philadelphia” [28]. The Presbyterians were encouraged by the report and sought not only to participate, but to lead the way in promoting the revival. Their efforts would ultimately cause the Revival to be remembered as a largely Presbyterian affair, despite the fact that there was some amount of Protestant cooperation throughout it. One account will suffice to show the ecumenical nature of the Revival: Present at the revival services in [Ballymoney], without prior arrangement, were the Church of Ireland rector, Rev Harry Ffolliott, and his curate, Rev George V Chichester, and the Presbyterian minister, Rev Jonathan Simpson. Already they were having united prayer meetings in Portrush. An open air meeting was held on 6 July on Ramore Head with some 2000 present. There were short addresses by the local ministers and “converts” from Ballymoney. That evening, it is believed, some thirty folk found the Saviour. Simpson records that at another open air meeting “an Episcopalian clergyman, a Presbyterian minister, a Congregationalist and a Baptist took part” [29]. Meanwhile, in Belfast, Academy Street Baptist Church welcomed the news of God’s work in Canada as delivered by Rev. R. M. Henry. Henry had previously been a Reformed Presbyterian minister, but had by then become a Baptist. He encouraged the Reformed Protestant minister in Cullybackey, Rev. J. G. McVicar, to also become a Baptist during the Revival. McVicar would go on to form the Baptist church of Ballymena, which prospered in the Revival. In summarizing the Revival itself, supporters ...claimed an estimated 100,000 converts and discerned the positive effects in increased family worship, church attendance,numbers of communicants, prayer meetings, Bible distribution, Sunday schools, open-air preaching and denominational unity, as well as the decline of immoral behaviour such as gambling, intemperance, prostitution and Sabbath desecration [30]. Revival ControversyThe hallmark of the Revival, according to the Presbyterians who championed it, was the sobriety and sensibility of it. The Revival was touted as being the work of God, with the people taking no liberties in relying on emotion to see converts. This view of the Revival was crucial not only to suit the existing Presbyterian hopes for an orderly revival, but to verify the event as legitimate. It was argued “that one of the reasons the revival was genuine was because it ‘[had] sprung up amongst a people staid and sober to a proverb – very different in temperament from the impulsive Celts of the South and West – a people, in fact, not strongly emotional, and peculiarly exempt from superstitious and fanatical feeling’” [31]. Aside from the problems that arise from making such distinctions among the people living in Ireland, especially when it seems to view the Irish themselves as lesser individuals, it was also likely an inaccurate description of the revival itself. Opponents to the Revival saw a vastly different story unfolding. Their concern largely focused on stories about manifestations that “occurred in a variety of geographical locations and took different forms including stigmata, ‘convulsions, cries, uncontrollable weeping or trembling, temporary blindness or deafness, trances, dreams and visions’, though prostrations were the most common” [32]. These are generally considered to have been relatively rare occurrences that were exaggerated by the press, but they were undeniably a factor in the Ulster Revival despite having no presence in America or the initial waves in Connor. This concern was raised during a June 1859 meeting, in which “the Presbytery of Belfast was positive towards the revival but wary of the manifestations. Professor J. G. Murphy expressed his disapproval and stated his preference for ‘the silent workings of the spirit of God, as likely to be more lasting’. Gibson likewise stated that he ‘had no sympathy with those extravagances’ and recommended a cautious approach” [33]. William McIlwaine, in studying the event and Presbyterian history, came to the conclusion that the manifestations and chaotic nature of some conversions held more in common with the Six Mile River Revival than previous Presbyterians had claimed. He and Isaac Nelson were also concerned about American revivalism in general, and wrote extensively on the subject in Ulster papers. Their major point of concern was that “the revivalist religion of the American Churches led to moral prevarication that permitted slaveholders to remain church members” [34]. They held that, if revival was not sufficient to make the church address and mourn its nation’s most glaring sin, then it was not changing hearts. Ultimately, however, McIlwaine and Nelson remained in the minority, and the effects of the Revival went on without them. Consequences of the RevivalSmaller Protestant denominations fared better in the wake of the Revival than Presbyterians did. According to Ulster census records in the decade following 1859, “the number of persons in the ‘Other’ category, which included Baptists, Independents and Brethren assemblies, rose from 20,443 in 1861 to 35,098 a decade later, while the number of Presbyterian declined by more than 26,000” [35]. By the end of the century, Ireland boasted “thirty-one Baptist churches, with two thousand six hundred and ninety-six members” [36]. This was despite a drop which occurred when both Henry and McVicar left the Baptist denomination to join the Brethren movement in 1863, taking a large number of congregants with them from their own churches and others. The Revival also had very little impact on the state of the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland. While some accounts mentioned Catholics converting during the Revival, “it is clear that the revival made little impact upon the Catholic population in Ulster, none at all in southern Ireland and there was little or no effort made by the Protestant Churches to evangelise Catholics” [37]. The Presbyterian church did not gain the political power over the Catholic church that it had been seeking, but did solidify its position as part of an Ulster-Scots identity. That identity would go on to fuel unionist rhetoric when the rest of Ireland sought independence from England, and heavily influenced the politics of the new Northern Ireland when the island was eventually split in two. The wave of revival did not stop in Ulster. Scotland and Wales saw revivals in that same period, and In 1860 special prayer meetings were organized in London and, under the leadership of the famous Lord Shaftesbury, a series of Theatre Services were held. At a number of other centres in the metropolis, and throughout the country, popular evangelistic services took place. The supporters of the Evangelical Alliance were to the fore in these efforts, but the movement had the support of other circles as well. Most Baptists co-operated wholeheartedly [38]. The full impact had not died down on either Ireland or Great Britain before D. L. Moody arrived, and this period is “generally accepted as the second phase of the 1859 Revival” [39]. This wave of revival would once again hit Ulster and Wales, the latter leading into another revival in 1904 that would overflow back to the former. The success of the Revival was largely measured by the experiences of those in it, with doctrine becoming a secondary issue. Supporters of the Revival pointed to individual piety, a clear moment of conversion, and social factors such as temperance as evidence of the work of God. The concern about personal piety and experience started a shift in Presbyterian thought, where “theologians increasingly saw religious experience as the essence of Christian faith and placed it at the centre of their inquiries, characterising the Bible as a record of the developing spiritual experience of humanity rather than as a manual of doctrine” [40]. The battles fought within Presbyterianism at the beginning of the nineteenth century, which solidified a more concrete conservative nature to the denomination, came under a new assault as “the use of the language of experience...allowed some opinion-formers within the Presbyterian Church to adopt higher criticism and to be accused of promulgating so-called modernist theology. Those sympathetic to modernism could separate the text of Scripture from the spiritual experience to which it gave witness while the laity could retain their pietistic spirituality” [41]. Baptists did not seem to fall into this same error at the time, but once the idea was in place, it would arise again; the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy that split almost every major Protestant denomination in the early twentieth century can be largely traced back to the debates within Presbyterianism in the years after 1859. Both Northern Baptists and the Southern Baptist Convention would end up having this same fight in the twentieth century, with the fundamentalists breaking away in the north to form the Conservative Baptists of America while modernists were driven out of the Southern Baptist Convention. The Irish had been increasing their attempts to control their own land in the wake of the potato blight, when it was shown (in the most charitable wording possible) that the British concern for the island was insufficient to the needs of its people. Having entered the revival period with little outside help and growing problems, the Irish Baptists came through the 1860s with a growing body and a renewed vigor for the work ahead. It was enough of a head start that, with 29 churches, “the Baptist Union of Ireland was formed in 1895 and links with the Baptist Union of Great Britain were severed” [42]. While political independence would happen for the Irish later, the Baptists of the island had achieved some measure of religious self-determination. ConclusionIt is worth noting the contrast of approach and results. Where the Presbyterians sought to dictate the expression of revival and use it for political ends, they not only failed, but suffered losses and endangered their view of scripture. Where the Baptists, Brethren, and other small Protestant groups embraced work God was already doing and submitted themselves to take part in it, with no political ends or means, they saw growth and enjoyed, if only for a short time, a unity of purpose and blessing. Baptists played a significant role in the Ulster Revival of 1859 and benefited greatly from it, even if they are hidden in the shadow of the Presbyterian work. What had been a struggling body of believers barely holding on to its place in Ireland had come to stand on its own feet. The place they carved out for themselves is still growing, although slowly. One woman presenting Christ to a young man in County Antrim, and one man sitting down to pray with the doors open for others to join in New York City, were used by God to change the character of Christianity in Ulster and the greater United Kingdom. This seed was not too small to see a revival--perhaps the Baptist churches of Ireland are not too small a seed to see an even greater movement of God today. FootnotesNote: What follows is adapted from a paper written for my college course, Baptist History and Distinctives. This was originally written in March, 2018. The assignment was to identify what we felt to be the most important Baptist distinctive and then discuss it. Given that I also get asked offline what, exactly, a Baptist is, I felt it was worth adapting here. When asked to describe the basics of Baptist theology, the easiest way to answer is to describe the parts that are most visible. The Baptist believes in believer’s baptism, through immersion, given no earlier than the baptized is able to make a true confession of belief and has done so. The Baptist believes the elements of communion to be fundamentally symbolic, bringing to mind the work of Christ. One may even go political and talk about the historically Baptist argument for the separation of church and state, or the ways Baptists have been seen interacting with the modern political environment. However, at the core of all of this, and much more, is the Baptist concept of the believer’s church. The Baptist, and those who have borrowed theology from Baptists, holds a view of the body of Christ manifest in the world that is distinct from other streams of Christianity and produces all the visible practices of the local church.

At the core of this issue is the question of what the church is. If the church is basically a regional expression, a sort of divine government over a parcel of land, then it should make sense that people be incorporated into it based on their place of birth, as citizens of both a physical and a spiritual nation. However, there is no trace of this idea in scripture. If Paul could say to the church in Corinth, “now you are Christ's body, and individually members of it,” then the church must be defined by its relationship to Christ (1 Cor 12:27 NASB). That is, in order for the church to be Christ’s body, the church must be in Christ - and no one is in Christ who has not been redeemed by him. If the church are specifically those who have become “dead to sin, but alive to God in Christ Jesus,” then there can be no one in the church who are not yet dead to sin, and only those who have been made alive in Christ can be members of it (Rom 6:11 NASB). So the Baptist holds that the defining trait of the church is that it is the body of Christ, or more specifically, the gathering of those who are in Christ into one body. This doctrine naturally flows into all others by which the Baptist can be recognized. If the body of those in Christ gathered is the body of Christ, then the local church is able to stand as the body of Christ. The local church is independent, not reliant on a larger body whether religious or secular for authority to operate as Christ’s body, and has for itself Christ as its head (cf. Col 1:18). This frees the local church not only from the structures of a larger religious body but also from the dictates of any mortal government. The local church is an expression of the fullness of the body of Christ just as Christ, though finite in His body, was able to express the fullness of the infinite God while walking the Earth. This enables the local church to carry out the full mission of Christ’s body in the world without borrowing authority from a larger structure, including ordaining, releasing, and holding accountable their own leadership; while leaving the local church free to partner with other local churches as equals. If the church is composed of those who are in Christ, then the mark of entry into the body must be given only to those who are in Christ. The idea that baptism is the mark of entrance into the church is not specific to Baptists - most, if not all, denominations would agree with that claim. The different ideas on when baptism should be applied are based not on the function of baptism, but are fundamentally built on differing ideas of what the church is and therefore who receives entry. As stated above, a view of the church that equates entry with physical citizenship must baptize immediately, as the child is understood to be in the church at the time of birth. A belief that the church is the gathering of those in Christ’s body, however, demands that baptism be withheld until a person is actually in Christ’s body. This also informs the difference between those bodies who believe that baptism has any ability to save or impute grace onto the baptized, and the Baptist who believes it to be only a sign. If baptism is applied after one is already in Christ, then the baptism itself cannot hold any power to place one into the body. It cannot change one’s nature into that which it already is. In fact, all ordinances of the church must be symbolic. If a person can only be in the church by already being in Christ and redeemed by Him, then no practice of those already in the church will have the power to bring people into it. Baptism cannot redeem because it is applied to the already redeemed, and the same goes for the taking of bread and wine in communion. The body and blood of Christ have no need to be physically present in the bread and wine because the body gathered is the physical manifestation of the body of Christ already. Christ is present in a special way whenever and wherever His people are gathered, they do not need to invoke Him into presence through another medium (cf. Matt 18:20). When one is asked to define the distinction Baptists and Baptist-like bodies have with all other groups of Christians, the answer must begin with the doctrine of the believer’s church. All other things that define the Baptists as a specific and unique movement are born from this doctrine. However, the need to grasp this distinction goes beyond simply defining Baptists to those who are not Baptists. Keeping this understanding in mind also enables the local church to hold itself, its members, and its leadership accountable to its effects. The local church, as the body of Christ, must be working on the mission Christ has given it. The church must be vigilant that it recognizes those who are in Christ and refrains from giving undue authority to those who are not, whether they are attending church services or sitting in positions of political power. In order to faithfully carry out the identity Baptists have, the individual Baptist must know what that identity is- and it begins by grasping the doctrine of the believer’s church. |

Scripture quotations taken from the NASB. Copyright by The Lockman Foundation

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed