|

Note: What follows is adapted from a paper submitted as part of my education under the Antioch School. The requirement for the paper was that I design "a set of guidelines for establishing local churches anywhere according to an advanced biblical understanding of Paul’s concept of establishing local churches, including instructions for 'house order' of local churches."

If our work is to be establishing churches, then we need to know how to establish churches in a way that is flexible enough to fit into contexts as widely different as first-century Jerusalem and modern New York, rigid enough to do the work Christ has intended for the church without straying from His intended model, and drawn from scripture as the normative expectations Christ and the apostles had for the church. The process we see Paul implement time and again essentially falls into three stages: assemble a body, impart solid teaching, and entrust to established leaders. This article will explore a definition and the necessary elements of each step.

We see more of this work in Acts than in Paul’s letters, largely because Paul was often writing letters to bodies he’d already assembled. There is limited exception to this, in that Paul occasionally gives instructions to his recipients on how to identify people who should not be in the body and thereby performs work related to, but not actually within, the assembly stage. Throughout Acts, however, we see the initial practice in more detail. Jesus assembles His followers and gives them instruction to wait as a body for the work He has for them to commence.(1) In response to Peter’s sermon at Pentecost, those who believe are baptized into the body and begin sharing their lives with one another. Paul consistently goes to a gathering place (usually a synagogue), delivers the gospel message, and then sets apart those who believe into a new body.

Even when we see individuals become Christians, they do so in community. Cornelius and the Philippian jailer are both saved alongside their households, Apollos is familiar enough to the church of Ephesus after his conversion that they were willing to send a letter vouching for him when he traveled to Corinth in the very next verse. We tend to focus on Paul’s miraculous encounter with Jesus on the road to Damascus, but his conversion was not complete at that point; the Holy Spirit doesn’t descend on Paul, a repeated sign for the moment of true conversion in Acts, until Ananias comes to welcome Paul into the church body. There is, in fact, only one exception in all of Acts: the Ethiopian eunuch is not immediately brought into a local church body when he is baptized by Philip. Church history tells us that he brought the gospel back to his own country and a community of faith was immediately formed there, but we have no record of this in scripture. The oddity of this event is, itself, indicative of how the alternative is the accepted norm throughout scripture. I am of the belief that every valid(2) denomination and theological movement within Christianity is really good at highlighting at least one, but not more than a small handful, of truly important elements of the faith that other denominations or theological movements overlook or undervalue, and that we would benefit greatly by more deeply considering these pockets of truth we can learn best from outside our own traditions. Sometimes they become so absorbed by this truth that they let something else wither entirely or develop a wrong understanding of a related concept out of misplaced focus, but the foundation they are using for this is still worth understanding. This is one area that I would argue the Roman Catholic Church has us at a theological disadvantage: there really is no salvation outside of the church. The See has, in some times and in some ways, taken this to a questionable place, but the proper solution cannot be the rugged individualistic salvation we have accepted so long in Baptistic, Pentecostal, and other related environments. We are not, I would argue, saved as individuals; rather, we the church are saved together.(3) Upon adoption as children of God, we are brought into communion with the rest of His children. We are members of the body, indeed, we cannot be outside of the body of Christ without being apart from Christ. Salvation inherently gives us a body to which we belong, and our growth must happen within the context of that body. There are few places where this is more apparent than in a church plant. I have been a member of four church planting teams, one of which I led, and these have produced some of my closest relationships to date. The scope of the work, when faced with a small band of Christians, pushes people in a distinct way. I have heard much about how church planting work tests one’s faith and missional focus, quickly weeding out anyone not prepared for the work and any aspects of our lives that interfere with the work, and this is all true; but I have heard significantly less about how it connects the people involved. My wife and I have grown considerably in our relationship through the ups and downs of church planting. When we were working in Greenfield with one other couple, we became family. Our kids were constantly together and began to act like siblings, the mother of that family is still my wife’s best friend; a divorce and seven years later, and we make a trip to New Jersey every year to see her and her husband and the kids even when we don’t have the means to visit my biological family the next state over. We all grew together, we invested in one another, we hurt for one another, we rejoiced together, and although no lasting church was established in Greenfield from that work, I believe we have displayed the kingdom of God more accurately alongside them than we have in many churches with longstanding buildings and budgets. We have another family with a similar level of connection, and that grew out of working together on a church planting team in Fitchburg. The mistake we make too often is conflating the importance of unity with the styles we use in our gatherings. We are commanded not to forsake the assembly; we are nowhere commanded to sit facing a stage and listen to a half hour lecture. I don’t have much against our modern practice of gathered worship—other than the strict rigidity with which we practice it—but this structure is not essential and is, at times, detrimental to that which is essential. That is, getting everyone together at a specific time on Sunday morning, singing a set constant number of songs, praying at scheduled intervals, listening to a sermon, and receiving a benediction is not a bad model in and of itself, but our insistence on it as “what church looks like” diverts our attention from how the church is actually intended to function. It’s easy to view our unity as defined by how many of us are sitting in the same room at the same time hearing the same message, but that isn’t where the unity of the body is practiced, and having the room become too large makes it impossible to practice any real unity. The body, in order to look like the church as established by Christ, must be grounded on intimate relationship guided by solid teaching under the authority of established leaders. The guidelines for proper assembly, then, are that the body is gathered in an environment that facilitates and encourages intimate relationships, the body invests in the spiritual growth and practice of spiritual gifts by all members, the body puts structure as secondary to purpose, and the body is prepared to send out members to establish a new assembly before it grows too large to accomplish the previous guidelines. There are a few concrete ideas that arise from this—such as the need to have some offline connections and relationships and gatherings, the need to guide spiritual formation in the proper way of Christ, and the need to send out church plants rather than growing too large for deep community—but much of the practice of this will be contextual and must be flexible to be applied correctly in different environments and with different people. If the purpose of the church involves the healthy growth of Christ’s body, both by multiplication and by maturity, as this blog has argued it does, then the structures that accomplish that purpose must be curated to the place and time and people to which it ministers.(4) These guidelines direct the boundaries of that flexibility, but must remain broad.

The assembled body must be built upon and maintained by the truth of who Christ is and to what He has called us. The way we ensure this is through deep, consistent, and accurate teaching, delivered by some number of established leaders who are faithful to the truth of scripture. This teaching is broadly concerned with a right understanding of God, a right understanding of our relationship to God, and a right understanding of our relationships among ourselves.

A right understanding of God is the basis of all theology, and is concerned with the nature and works of God in all matters. Every other teaching flows from this; everything about the church is defined by who God is and what He has done and is actively doing and will yet do. Here is covered such topics as the nature of the Trinity,(5) the person of Christ, the work of salvation, and God’s ultimate victory at the end of the age. This topic is vast, and must be constantly revisited and expanded upon in order that its application in the other topics is held to the standard of truth. A right understanding of our relationship to God is focused on who God is to us and who we are to Him. This topic tells us about our need for salvation, how our salvation has changed our standing before God, and how we are to grow in the new life to which God has called us. Here we see how submission to God is imaged in our submission to church leadership and the submission of wives to husbands and children to parents, how the mission of Christ has been handed to the church and therefore what goals the church must seek to achieve, and what it means to become children of God and heirs of His promise, among others. This teaching must be delivered frequently to ensure the church is aligned with its role in God’s plan, but it must also be a source of guidance for all the church does as a body and how the church invests in individuals. The first topic tells us what God we serve; this topic tells us how we, as a body, best serve Him, and must be always on our mind and in our teaching to ensure we approach our mission properly.

A right understanding of our relationships among ourselves guides our understanding of life within the family of God. This topic is about how we engage with one another, what authority and submission look like in daily practice, and how to live out the love that Christ has poured out so lavishly on us. Here we get into the nuts and bolts of the house order, describing the terms of our submission to authority within the church and within the home, detailing the practice of the nested dualities I covered in a previous post, applying the calls in scripture to view others above ourselves and love our neighbors as ourselves. This teaching is almost always an application of one of the other topics, but is important and must be included whenever application is being delivered. Our assembled body must be guided on how to be an assembled body, and this topic concerns itself with that more than any other.

When I was planting in Greenfield, I mapped out a sermon series that lasted one year as our very first study. Essentially, it worked through the Old Testament and sought to understand its themes through the lens of Christ, beginning with creation and ending, at the beginning of Advent, with Christ as the culmination of all the other things we’d discussed. The aim of this study was multifaceted; it revealed how the work of God and the heart of Christ was present throughout all scripture, it focused our attention on Christ in all matters, and it trained us to see Christ as the focus of every story and every theme throughout the Old Testament. The idea was that new people coming into the church would learn who God is through His dealings with mankind, and established Christians would be reminded of the role of Christ in redemptive history and the application of the Bible’s lessons. That the church would begin rooted in this understanding and what it means for us. I was not able to finish the series before the church folded, but have kept the basic outline just in case I have opportunity to explore it again. Because this is the nature of the guidelines for imparting solid teaching; that established leaders point to God through His word to reveal His nature, call the body to live in light of our role in His purposes, and guide the body to daily lives reflecting the truth and glory of God among us. That teaching plan I started to put into practice was aimed at these very objectives, but obviously it is not the only way to apply these guidelines. The objective is simple: teach often, teach faithfully, and apply the teaching to every aspect of the life of the church and the lives of its members.

Paul, having bound a body together and delivered the word of God faithfully to them, identified those who were gifted and growing in maturity in such a way that they could be trusted to continue the work after he was gone. These were drawn from the body itself and placed into the role of leadership, held to a higher standard to ensure they were fit for the duty, and taught the functions of a leader to properly guide the body. These people were expected to teach faithfully, to protect the body from false teaching, to maintain the house order of the church body, to carry out the work of church discipline, to identify and train new leaders, and to send out parts of the body to establish new bodies as appropriate.

Paul details the means for selecting these leaders in his letters to Timothy and Titus, but their work is constantly visible in all his letters. The leaders were the ones expected to impart the teaching Paul was including in his letters, they were the ones being called to oversee any acts of discipline Paul called for, and they were responsible for the daily application of the principles Paul explained. Peter directly addressed his letters to the leaders themselves because of these responsibilities. In the house order, the leaders were those who held the honor of leading and directing the church, and the responsibility to do so in a manner that glorifies God and serves His purposes. The leaders are those who impart the teaching, who guard the body, who constantly refocus the body on Christ to ensure He is the foundation of the body’s work and unity. The guidelines, then, are that the church has leaders in place who have been properly identified by an established church body and trained in service to Christ, who maintain the standards of leadership described by Paul, who are treated as authoritative by the body, who are able to teach and willing to correct, and who are able and willing to identify and train new leaders. These leaders should be placed within the biblical duality of elders and deacons, with the office of elder reserved for men. There must be a plurality of leadership; one man’s mistakes cannot be given enough power to damn the mission of the entire body.

The guidelines which must shape all churches in all places and times, then, are the broad ideas illustrated through these areas of concern. That the church must be an assembled body living in deep relationship that glorifies God, taught faithfully on the nature of God and the work He is doing in and through that body, under the authority of established leaders who center the body on the truth of God and guard it against distraction and alternative purposes. Establishing a church is the process of putting all these guidelines into place and fulfilling them, leading to the spiritual maturity of the body and its members. Our flexibility within them is necessary to engage with where God has us and who He has put into the body, and we should try to mold our systems to our context rather than being ruled by the systems we’ve inherited. But these guidelines are to be respected both as a direction to aim and as boundaries to what we cannot do; the body of Christ can no more tolerate a lack of leadership or the presence of bad leadership than our mortal bodies can tolerate cancer. We can bend within the principles described by Paul, but cannot break or try to escape them.

Footnotes

0 Comments

Note: This is adapted from a paper written as part of my studies at the Antioch School. The objective of the assignment was to demonstrate that I had "developed an advanced biblical understanding of the philosophy that is to drive the ministry of the church and the instructions (i.e. “house order”) by which each local church is to abide."

In my last post, I argued that submission to roles within the body, and allowing those roles to be defined by Christ rather than purely pragmatic or social demands, was a crucial element of aligning our churches with the design found in scripture. That our practices needed to be primarily defined in light of the community of faith Christ is building rather than personal interests or cultural norms. Here, we turn our attention to what that looks like in practice. This primarily arises in two categories; first, the specified roles that exist within the church, and second, how those roles interact in key circumstances as part of the life of the church.

The actual roles within the house order in scripture fall into a series of nested dualities that ultimately reflect the relationship between God the Father and God the Son to varying degrees. The Father is the supreme and perfect authority; all things are in subjection to Him, and He carries out His authority in pure love. The Son is the perfect agent of the Father’s will, doing all He does in submission to the Father and joyfully glorifying the Father through His every word and deed. In all of this, the Holy Spirit unites and glorifies, participating in and highlighting the love that exists within the Trinity and pointing to both the Father and the Son in all things.

The relationship that exists within the Trinity is fundamentally one of love, in which the Father loves the Son and the Spirit, the Son loves the Father and the Spirit, and the Spirit loves the Father and the Son, and there is no partiality or brokenness in these loving bonds. The three are one, truly one, such that we worship but one God in three persons. No person of the Trinity is lacking in anything, not even honor or power. The Father is not more God than the Spirit or the Son; every person of the Trinity is fully God and, therefore, fully empowered and worthy of all praise. The roles within the Trinity define the interpersonal relationships within divinity, but do not elevate or denigrate any person to any position other than True God. This is the defining nature of the roles of the church. Every role within the church is engaged in presenting an image of this Trinity relationship, and every interaction among the body of the church is to display the pure love and true bond found among the persons of the Trinity. We must have this understanding in place if we are to carry out these roles correctly; we cannot emulate that which we do not know. We must also recognize the limits of our understanding and of our roles. We cannot perfectly understand God, or at least, if we shall ever perfectly understand Him it will not be on this side of eternity. We cannot perfectly practice the love of the Trinity within our own bodies, as we are not perfect agents of love while yet in these bodies. No roles within the church are perfect images of the divine nature, for a multitude of reasons, but a key one that warrants mention before we continue is that there is no role in the church that has absolute authority the way the Father does. Every leader in the church is also a servant, as Christ noted when He said, “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great men exercise authority over them. It is not this way among you, but whoever wishes to become great among you shall be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you shall be your slave; just as the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life a ransom for many.”

|

Dualities in the House Order

|

|

Second, a note about terminology. I do not mean to describe a duality as a pagan may use the term; these are not sets of equal but opposite forces that find their purest expression in appropriate balance. Rather, they are two pictures that, taken together, present a larger picture. There are ways they are equal and ways they are not, but in a healthy church environment, they are never at odds. Fulfilling our roles well means that we are separate only so that we can be seen as united. A unity without parts is not a unity at all, but a single thing; for our images to work in a way that displays unity, then, there must be parts1. In God’s design, these parts are arranged in pairs that nest within and relate to one another.

While not every duality here will get equal weight of discussion in this paper, these are the essential ones for consideration as we move forward. The relationship between God the Father and God the Son is the template, and each will be listed in that order (that is, the member imaging the Father will be listed before the member imaging the Son). The primary dualities are the Son and the Church, the Church and the Home, and the Church and the World. Within the church is the duality of Leaders and Congregation, and within the leadership are the Elders and the Deacons. Within the home are the Family and the Servants, within the family are the Parents and the Children, and within the parents are the Husband and the Wife. Lacking some element here is not utterly devastating; a household without servants, for instance (which is most of them now), simply lacks that role. We are concerned here with how those roles work together to image God, not any debate about whether or not every role needs to exist in every place where it can exist2.

The Son and the Church

|

|

Likewise, the church is designed to operate with leadership in place that has the power to direct its operations and carry out church discipline. This leadership does not have ultimate authority; leaders of the church submit to Christ as Christ submits to the Father, and serves the body as Christ has served the church in His laying down His life for it. This was discussed in more detail elsewhere, but essentially, a church cannot be a church until it has leadership, specifically because it cannot perform its essential duties or maintain its adherence to Christ without trained leaders who point to Christ in their own deeds and in the relationship they have to the rest of the church body. Similarly, the church cannot be a church without a body that submits to the authority of the leadership as the church submits to Christ, since it is the body that carries out the work of the church in the world as the church carries out the work of Christ in the world and Christ carries out the work of the Father in the world.

Within the leadership are elders and deacons, the two offices defined in scripture for the governance of the church. Together, they are the leadership addressed in the paragraph above. But they have distinction between themselves, and within that distinction, the elders set direction as the Father sets direction for the Son (and as the Son sets direction for the church), and the deacons carry out the will of church leadership through service to the body as Christ carries out the will of the Father through His service rendered to the church (and as the church carries out the will of Christ).

Part of the work of church leaders is to direct the regular life of the church. This means that it is church leadership that ultimately calls and leads meetings of the assembled church body. The leadership keeps order at the assembled meetings, points all that happens to Christ, and carries out the essential functions of equipping and establishing the body. The congregation, then, follows the order as established by the leaders and submits to biblical teaching and direction as it is delivered during their times of assembly. Elders are described by Paul as having an ability to teach, because it is part of the fundamental nature of church leadership to pass on the knowledge and will of Christ to the body.

Relationships within the body are intended to showcase the patient love of Christ, as well as the importance of the church’s mission, at all times. As such, Christ gives us direction in Matthew to approach one another about sin and disputes in a manner that gives the offender multiple opportunities to repent and make things right, with increasing support from the church. When this process is not fruitful, however, Paul operates on the understanding that it is the leadership of the church that holds the authority to discipline the wayward member. Gilliland argues that this responsibility is a natural expression of the patient love expressed in the Matthew process when he says, “The Christian who lapses into unchristian behavior requires patience, much teaching, and genuine caring and love. The discipline of the Christian church must be the work of those who have a truly pastoral heart.”3 That is, the heart that qualifies one for church leadership is the same heart needed to practice discipline within the church in a manner that respects the offender and emphasizes the proper mindset of the church toward the offense.

Disruption of these relationships, then, not only alters the practices of the church, but corrupts the image the church is meant to be displaying. If the deacons operate as elders, or the body operates without leadership, or the elders fail to submit to Christ or serve the body, then the essential function of the church—as the manifested glory of God in the world tasked with carrying out the redemptive mission of Christ—falls apart.

The Church and the Home

|

|

Photo by Redd on Unsplash

Photo by Redd on Unsplash

The home, similarly, has offices, and there are specific elements of church life that happen within the home. The finances of the church, for instance, come from the finances donated through the homes; if the homes within the church do not understand their responsibility to support the work of the church with their resources, and do not graciously and joyfully give of their resources to the God who provides for them, the church will find itself lacking and struggling to afford its basic tasks. This then cycles back into the homes, as the church is called to provide for any among them who are lacking. This is seen in the creation of the office of Deacons, whose first task was to oversee the support of widows, and James 1:27 reminds readers that concern for widows and orphans is a crucial element in the life of the church and the believer. As those homes with resources give those resources to the church, the church has the means to provide those resources to the homes that lack. In this way, the relationship between the church and the home is not only reflective of each other, but cyclical in practice, much like the love that flows eternally between the Father and the Son.

In Ephesians 6, Paul describes various relationships within the home and shows the image of the Father/Son relationship in them. Servants (or slaves in some renderings) submit to the authority of their masters as Christ submits to the Father, not merely in grudging action but in sincerity, while the masters are commanded to treat their servants with a sincere and respectful heart that mirrors the way the Father directs the Son. Children are called to honor their parents, while the parents (namely the fathers) are called to a mindfulness in how they raise up their children without unnecessary provocation.

But these are presented in light of the longer text (Ephesians 5:22-33) before it, which details the relationship of the husband to the wife. Paul explicitly states the image-bearing nature of the marriage relationship repeatedly throughout this section, pointing husbands to the part of Christ and wives to the role of the church. He points to the self-sacrificing love of Christ for the church as a normative expectation for the love of a husband for his wife, framing the submission of the wife as a healthy response of a woman enjoying the grace and support her husband shows her rather than the fearful response of a woman under the command of an abusive or demanding husband. In this way, also, the marriage images the church, where the husband encourages the growth of the wife toward her full potential in faith in the same manner as Christ builds up the church and calls it to growth toward its full potential in faith.

Incidentally, it is the image-bearing nature of the marriage relationship that sorts out a number of questions the church receives about other gender-related issues. By lacking the interplay between a man and a woman, a same-sex marriage is incapable of displaying the same image as a man married to a woman, and therefore the marriage displays a false (or at least incomplete) picture of the relationships it is meant to display. The role of elders within the church in their relationship to deacons, serving the same functional role in its image duality as husbands to wives, is sensibly limited to men, while the role of deacons is not.

Note, however, that this overall structure does dictate when and where the church has authority in the home. The relationship of the church and home is essentially big-picture; the church gives direction to the home, but the relationships within the home dictate how that direction is actually carried out. The elders do not have authority to replace the role of parents in the lives of children, but do have a requirement to hold the parents accountable to whether or not their parenting actually serves the greater mission of the church. The church cannot tell the wife whether or not she’s allowed to work out of the home, as this is a matter that falls within the means of the home governing itself; but must ask stern questions of the husband if the wife isn’t growing in her walk with Christ, as this would suggest a breakdown in his role to support her growth as Christ supports the growth of the church. Ultimately, each relationship being described falls under the broad direction of the relationship in which it is nested, but retains some autonomy in its actual practice. Which sets us up to discuss the final category of relationship relevant to our topic.

The Church and the World

|

|

First, note that the church is called to be above reproach from the world; 1 Peter 3 and Romans 13, for instance, urge that the behavior of the church toward the world be pure and unblemished by evil, with the intention that the world sees the goodness of God and responds in faith. Compare this with the call of elders to be above reproach in 1 Timothy and the role of husbands as faithfully and lovingly guiding their wives to greater knowledge of and faith in Christ. In this way, the church leads the world toward God, even if only by example.

Second, our showing loving guidance toward the world is self-sacrificial, as Christ’s love for the church is. We are called repeatedly to lay down our rights or lives, if needed, in service to pointing the world around us to Christ. We are to rejoice in trials, accept any trouble brought to us for doing good (while striving to have no trouble brought to us for doing evil, that is, avoiding such trouble by avoiding doing evil), and recognize the authority of the world so far as it exists.

This last part is essential; there are areas where earthly authorities really do have authority, and we as the church show our submission to God through our submission in these areas. Where the laws of man call for taxes, or honor, or participation in civil engagement, to the degree that those things do not compromise the mission of the church, we are to render what is being demanded. Homes, essentially, have dual citizenship. They are subject to the church, and they are subject to earthly authority. Where these things clash, a Christian home must submit primarily to the church; where they do not, a Christian home must be faithful to both.

Every relationship within the church, then, is always engaging with the world. And in its engagements with the world, each must seek to point to Christ in all things, to glorify Him in their dealings with each other and the world, and to practice their relationships as images of the patient love that exists between the Father and the Son. By recognizing how each relationship in the life of a Christian reflects the other relationships, and looking at each as images of the divine love within the Trinity, we can more readily understand the nature of our roles and how to faithfully live them out.

2 Some roles are more necessary than others, but this is not a matter for this paper.

3 Gilliland, Dean S. “Growth & Care of the Community: Discipline and Finance.” From Pauline Theology & Mission Practice, 237–246. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1983. 243.

4 Banks, Robert. “The Community as a Family.” From Paul's Idea of Community: The Early House Churches in Their Historical Setting, 52–61. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1980. 54.

Photo by Clotaire Folefack on Unsplash

Photo by Clotaire Folefack on Unsplash It is important to think critically about the things we've come to see as defining elements of the church, asking whether these elements actually arise from a Biblical model of the church structure and, if not, asking where they originate. Being extrabiblical does not mean that an element is wrong, simply that it is cultural; cultural elements have their place in the life of the church, it simply isn't a foundational place. As such, we have to identify the major areas in which we have allowed extrabiblical sources to define the ministry of the church, how those sources have drawn us away from a biblical understanding, how to correct that shift, and where possible, how to use those sources in service to the biblical philosophy rather than allowing them to serve as an alternative to it. In our class time, we identified three major extrabiblical philosophies that have replaced that philosophy described by Paul and the other apostles in whole or in part. These were individualism, egalitarianism, and theocratic systems.

Individualism | |

The problem, however, is that it isn’t suitable as a foundational ideology. This is because, by design, allowing it to be foundational requires that the structure and practices of the church be fluid in ways that the Bible does not prescribe or condone. A church defined by individualism exists primarily to serve its members in a manner that is subject to their every whim. In fact, this goes even farther, in that an individualistic view ultimately attempts to stand in judgment of reality and its Creator. Consider what has come to be known as The Problem of Pain. Essentially, this argument claims that, because humans experience suffering, God must be imperfect either in His morality or His power. But this entire argument relies on the claim that individual humans are the chief end of existence, and therefore benefit to individual humans is the ultimate moral good that warrants the full application of God’s power in all instances. This is individualism not only redefining the church, but redefining mankind and God Himself in the process.

The biblical model, however, centers God as the focus and ultimate beneficiary of creation (including mankind) in general and the church in particular. The members are in the body to serve God; submitting to His structure, serving on His mission, practicing His methods, and aiming for the work He has determined, all for His glory. Paul says as much in his description of individual roles when he tells the Colossians, “whatever you do, do your work heartily, as for the Lord rather than for men, knowing that from the Lord you will receive the reward of the inheritance. It is the Lord Christ whom you serve” (3:23-24, NASB95).

Christianity is, therefore, a top-down structure. God is ultimate, His will defines the structures that will serve His purposes, and individuals operate in submission to those structures in service to Him.1

Egalitarianism | |

Egalitarianism is a fundamentally pragmatic ideology, and it isn’t necessarily bad at achieving pragmatic ends. This is evidenced by the way egalitarianism is argued for in most circumstances. The basic line of reasoning tends to be that acknowledging an inherent limitation or criteria to a role excludes people who can perform that work as well or better than the people who are actually in that role. And this isn’t false, but it also isn’t grounds for determination about a role within the biblical concept of church ministry. That is, if the sole determinant for roles within the church was its effectiveness at completing a task, then egalitarianism would be a valid way to understand those roles, but this isn’t true.

The reason for this is that the work of church ministry isn’t primarily about results, but about submission. As stated in the previous point, the whole work of the church is about God’s glory, will, and mission. Roles within the body, then, must be defined by how they serve that end. Roles are part of the structure that is defined by God, and God alone, in His ultimate wisdom, has the means to determine their criteria and limitations. As it happens, the design God has chosen as the means to best bring Him glory and serve His ends is one in which the church community and the household carry the same, or mirrored, roles.

This is, as Clark puts it, partly because “early Christians wanted family and community to support and reinforce one another.”3 He then goes on to argue that, due to this intended relationship, divorcing one from the other—the community roles and the family roles—would undermine them both. When Paul is defining the roles within a household, he is necessarily also defining the roles within the church. When he defines the roles within the church, he is by necessity defining the roles within the family. In both cases, he relates the matter back to how it stems from and reflects the truth of God, either by explicit statement of the connection as in Ephesians 5:32, or by a more implicit reminder that he is applying a truth as in 1 Corinthians 14:33. In all things, the roles must be defined and practiced in the manner God has chosen because each role, and their relationships to one another, fundamentally say something about God. It is more crucial, in the biblical model of church ministry, that this image be as accurate as possible than that the role is functioning at a high level of efficiency.

These roles, as described in scripture, create a community and family that operate from an interplay between leadership and submission that displays the relationship between the church and God as well as relationships within the Godhead. This is, fundamentally, the point; the roles serve not simply to achieve goals, as egalitarianism would view them, but to display truth. The role of husbands and how it engages within the household, with its authority and accountability, displays and applies the essential principles that define the elders and how they engage with the church, which in turn display and apply the principles that define how the Godhead engages with the church and God the Father engages with the Godhead. The wife, subject to the husband but in a position of authority within the household, images the role of a deacon as it leads and serves the church, which images the church as it sits subject to Christ but is the means of Christ’s authority manifesting in the world, which images Christ in perfect submission to the Father while holding authority to send the Spirit and lead the church. Children, in honoring and serving under the authority of parents, image the body of the church under the authority of its leaders, which images the church in full subjection to God, which is empowered by and images the Holy Spirit who operates in subjection to the Father and the Son and seeks the honor of both. It is natural for us to impose a hierarchy on these roles, due to the habits we’ve developed that will be explored in the next section, but this reading isn’t natural to the text. A husband serving as a deacon with living parents will find themselves needing to hold all these images in tension, with one shining through more clearly in different contexts. Being a husband does not mean one can shirk the submission inherent to being a member of the church body simply because he holds authority in the home.

Egalitarianism, then, would have us replace the intention of the roles with the utility of the roles, and by doing so, redefine not only the roles themselves but the statement those roles are making about who God is. It therefore cannot be treated as a definitive grounds for how we approach roles within the church or the family, but that isn’t the same as saying it can have no use to the church. Egalitarianism, appealed to in a limited fashion and always in service to the biblical model of ministry, does serve as a reminder to analyze whether a criteria and limitation we have come to expect is actually inherent to the role, or has been artificially placed there by mankind. It points us back to the actual definition of the role, and the will of its Definer, as the sole arbiter on whether or not a given person can serve in that role. Allow me to draw this out in an example.

A well-crafted and powerful sermon that stirs the hearts of people but brings glory to the speaker is, by definition, an inferior sermon to one delivered through stutters and awkward pauses that points the hearers to behold the glory of God. No one would doubt that the former is a more skilled orator than the latter, and for this reason, pure pragmatism and egalitarianism would put him in the pulpit on those grounds alone. There is no reason not to in that model, and a host of arguments for efficiency to support the move. However, the biblical model of ministry would undeniably demand that place be reserved for the latter, since he more faithfully serves the role with a heart that seeks to glorify God. Egalitarianism in service to the biblical model would remind us that the latter is preferable even if he has not attended seminary and the former speaker has. This does not mean the latter should avoid growing his skill in the craft of sermon delivery, it merely addresses whether or not he should occupy that role at all.

Theocratic Systems | |

Theocratic systems are those where the seat of government is tied to, and presumably defined by, a religious order. I say ‘presumably’ because I believe an honest review of history would show that the civil system has, in every instance, done some degree of redefining the religious system as part of the act of integrating it. It is this alteration and integration that has crept into our churches as a model of ministry alien to the teachings of scripture. For Christianity, this process began with Constantine and has carried on through the political weight of the Vatican, state churches such as Russian Orthodoxy and the Church of England, and attempted sanctification of secular bodies such as the workings of the Religious Right.

In every instance, the church has adapted itself to the workings of the civil structures it is attempting to command. These structures rely on bureaucratic systems, so the church adopts bureaucratic systems. These structures exist to justify the will of the government as a civil ordinance, so the church begins aligning itself to justify the will of the government as a divine ordinance. With these and other similar changes, the church structure shifts, and over time, we have come to expect that this is the normative, traditional structure for a church to have. To the point where, when I was at a previous Baptist college, I was taught a six-page list of church committees as though they were, every one, a necessary element to any true Christian church!

As we discussed in class, it may not be necessary to actually dismantle every element of the church that has arisen through this process. Some have proven helpful in certain places and times, and some have become so ingrained into our culture that we would sacrifice ability to connect with the culture around us if we abandoned it altogether. But aligning with the biblical model of ministry does require that we are willing to dismantle every theocratic element that has taken root in our church structures. That is, every element of our church structure, even (perhaps especially) those we have taken for granted as inherent to the nature of the church itself, must be open to examination and subject to removal if it is found lacking.

A Biblical Model | |

Ultimately, all of these questions come down to one core: is this element of our ministry being done in service to God by His ordinance, or in service to anything else and/or by any other standard? In order to operate within the biblical model of ministry, we must be willing to take anything—no matter how important to us—that falls into the latter category, redeem what can be redeemed, and throw out whatever cannot.

2 A proper understanding of how these roles are to be filled and what they are to do is necessary for the application of this philosophy, however—in fact, I would argue they exist in scripture specifically as direct application of it—and while this is a fact that warrants mention, it does not change the fundamental claims of this paper.

3 Stephen B. Clark, Man and Woman in Christ: An Examination of the Roles of Men and Women in Light of the Scripture and the Social Sciences (Ann Arbor: Servant Books, 1980), 134.

Formatting note: As last week, I have chosen to leave this in bullet format partly because it seems to work for the objective and partly because I am currently plagued by the same recurring headaches that made me write it as bullet points in the first place.

- As established, the local church has a mission

- Great Commission, developing disciples, establishing churches

- In order to participate in establishing a church, the established and the establishing church are in some form of partnership

- Partnerships are fundamentally relationships in which resources are shared for a common goal without sacrificing identity

- The local church is an autonomous body with the ability to enter into partnerships.

- What does autonomy mean?

- Simply that a church is not required to be in partnership and can choose its own partnerships and methods without direct supervision from an outside agency or another church

- It should not be confused with church sovereignty, which would hold the local church completely above partnerships and accountability, though this confusion is common

- One result of this is the fact that the established church does not have direct control of the way the new church operates

- What does autonomy mean?

- Three broad generally-accepted categories of partnerships

- Churches

- Parachurch Organizations

- Secular Bodies

- There are subtypes, but that’s beyond the scope of this assignment

- The local church is an autonomous body with the ability to enter into partnerships.

- Churches

- The only partnership that definitely exists in scripture

- Arguments could be made to view Paul’s mission team as a parachurch organization, but I believe this to be somewhat inaccurate and anachronistic

- Acts does not discuss the church working with secular bodies

- Paul receives support from churches other than Antioch

- Paul organizes churches to support church in Jerusalem in epistles

- Shared mission, resources, methodology

- North Central Collective

- Local example in which four churches have agreed to a partnership

- This partnership includes a growing relationship, a shared vision and mission, shared resources, and agreement about how to best apply those resources to that mission

- Churches are in relationship and accountable to one another but do not have authority over one another

- Very good at highlighting the benefits of close, regionally-minded partnerships

- Southern Baptist Convention

- Large example in which thousands of churches have agreed to a partnership

- This partnership includes a shared vision and mission, a clear statement of agreed-upon doctrines (The Baptist Faith and Message), a large pool of shared resources, and agreement on channels that will apply those resources to that mission

- Churches are in cooperation and may have relationship and accountability on a local level, but have no authority over one another and have limited, if any, relationship on a national level

- Very good at highlighting the scope of work a partnership can accomplish

- The only partnership that definitely exists in scripture

- Parachurch Organizations

- Mission focus

- Engel & Dyrness argue that missions should be the “guiding hand in all the church’s programs” rather than simply one more program (p122)

- Missional authority lies with church

- “one of the lingering effects of the structure of missions created in an earlier day is the attitude on the part of many missions executives and missionaries that the churches are simply the source of resources—money and personnel, or perhaps gifts in kind.” - Engel & Dyrness, “The Church in Missions” from Changing the Mind of Missions: Where Have We Gone Wrong?, p122

- If the mission has been given by Christ to the church, authority on how the mission is carried out must rest with the church and not external agencies

- Churches must retain control of what their involvement in parachurch activity is and how they will engage with that activity

- Mission focus

- Secular Bodies

- Partner to the extent that churches can retain mission focus and control of own actions

- Separation of church and state

- The church is not to put itself as a whole under the direct authority of the secular government or any other secular agency

- The church does, however, recognize the authority God has given governments in certain areas and must respect that

- The church may accept direction from secular agencies on a limited basis on specific ministry activities

- Where the church wishes to engage with areas that a secular agency has authority, it will have to determine whether or not submission to that authority’s rules and systems in that specific ministry is workable with the identity of the church

- If it is not, the church may need to seek an alternative method

- Fourth category: Individuals

- We describe the church as family throughout Antioch School

- This is good and appropriate; the church is a family

- The church is also a partnership, and as such should have the ability to see every member as an active participant in its mission

- This is good and appropriate; the church is a family

- Paul talks about churches as people

- He addresses individuals

- He talks about the unity of the people in the church

- Passivity

- Engel and Dyrness cite studies that show only 10% of people in an average church are active beyond Sunday morning

- They conclude, as do many others, that the vast majority of people in churches are passive participants because of the institutional model itself

- We describe the church as family throughout Antioch School

- I propose an alternative to this conclusion

- The people in our churches do not view themselves as active participants because the church itself does not view them as active participants

- Our entire model of church relies on people sitting passively and receiving

- The vast majority of people in a Sunday service will do nothing because we don’t invite them to do anything

- We put the preacher on a stage behind a podium where there is clear, visible division between him and the body, and have him talk without any opening for engagement

- We have designated leaders who pray on the stage in front of the whole body without any engagement from the body

- When we have someone we believe is suited for ministry, we send them away to be trained for ministry somewhere else, away from laity

- Here, Antioch itself helps address at least that problem

- The only things we actually invite most people to do generally are give money and sing

- So often we interrupt the singing so we can tell everyone to sit down and listen to a special person do ‘special’ music

- And then we tell them “go out and put into practice what you have learned” and get surprised when what they have learned is that the work of the church is the work of someone else

- This is, I believe, part of the source of the issue Roland Allen is talking about when he says on p144 of The Way of Spontaneous Expansion, “We have looked upon such spontaneous activity,” speaking here of spontaneous individual mission activity, “as something strange and wonderful...we have not known how to expect it, we have not known how to deal with it, and consequentially it is not unnaturally more rare than it ought to be.”

- Many articles do not go far enough in their call for reform because they still ground themselves on the idea of encouraging people to get up and do something out there without telling us to start by inviting and training people to do stuff in here

- I believe that all of our other partnerships would be more clearly understood and actively engaged if we began by asking how we can view the church as a partnership, how we can treat the congregation as active participants in our gatherings, how we can train them to associate the Christian life with action

- If we asked what everyone in the body is bringing on a Sunday morning, and where we can have an opening for that to be put into action during every aspect of the gathering, without demanding conformity or enforcing passivity from the people

- In 1 Corinthians 14, Paul describes church gatherings as having everyone involved, bringing whatever gifts they have to the service and the service having place for them

- We know that Paul advocated for all this to happen under the guidance of established, trained leadership, and not as a free-for-all

- We know that Paul advocated for all this to happen under the guidance of established, trained leadership, and not as a free-for-all

- If we got into a habit of viewing one another as partners on mission, and learned to see how what unites the church is our shared faith and our shared mission, and see the places where we lay our own desires down for the advance of the mission and the places where we maintain our individual natures and habits and styles and gifts, and how all of this serves the larger purposes of God under the authority of established leaders, then I believe we would have an instinctive sense for how the church partners with other churches under the authority of Christ, how we partner with parachurch organizations without giving over things that belong to the church, and how we engage with secular bodies without losing our identity as a church on mission.

- All of these partnerships, all of these things I’ve talked about, I believe they all start right here, in our churches.

- If we can have churches that view themselves internally the way the Acts churches did, then we can have churches who engage with each other and the world externally with the same impact as the Acts churches did.

- The people in our churches do not view themselves as active participants because the church itself does not view them as active participants

So then, be careful how you walk, not as unwise people but as wise, making the most of your time, because the days are evil. Therefore do not be foolish, but understand what the will of the Lord is. And do not get drunk with wine, in which there is debauchery, but be filled with the Spirit, speaking to one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody with your hearts to the Lord; always giving thanks for all things in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ to our God and Father; and subject yourselves to one another in the fear of Christ.

Ephesians 5:15-21 (NASB)

| Consider the language we use when we talk about putting Christ at the center of our lives, or about how we can be a blessing to the body. Even when we talk about communal elements of the Christian life, we talk about them from an individualistic perspective. It's all about our personal prayer time, our personal time in the word, Me & Jesus time. But the context in which the New Testament talks about the church, and even about our growth as Christians, is almost never talking about one individual doing much of anything. Paul is never instructing people to engage with the body out of the overflow of the great benefits they, personally, have received. It is always about growing and operating as a body. And we should hardly be surprised at this, given that the first church shared all they had with one another. |

Note the passage that opened this article. It's part of a larger discussion on living lives that honor God, but note the communal nature of it. Throughout Ephesians chapters 4 & 5, Paul constantly ties the things he's saying to a group context. He talks about "bearing one another in love" (4:2), "equipping of the saints for the work of ministry, for the building up of the body of Christ" (4:12); tells us to "SPEAK TRUTH EACH ONE OF YOU WITH HIS NEIGHBOR, because we are parts of one another" (4:25), "be kind to one another, compassionate, forgiving each other, just as God in Christ also has forgiven you" (4:32), "walk in love" (5:2). Why? So that we, "being fitted and held together by what every joint supplies, according to the proper working of each individual part, causes the growth of the body for the building up of itself in love" (4:16).

See, the thing is, it's easy for us to think about our involvement in the body in terms that focus on us as individuals. We so often talk about the Christian life as though we are solitary cups that need to sit alone to be refilled, and then we can bless others with the excess that pours out of us. Or as batteries, that get plugged into the body to give it what energy we have, but then have to be unplugged and sent to recharge so we have something to bring when we return. And there is a certain sense in which this is true; we all have our own lives and we bring to the body that which is unique about us. We do not, however, primarily grow in isolation. When the New Testament addresses the Christian life, it addresses bodies of believers. It addresses churches, and expects them not only to grow together, but to grow because they are together. We do not grow in isolation any more than a finger can grow when separated from the body. Our priority, if we are to be the body we have been called to be, must be other-focused.

And the eye cannot say to the hand, "I have no need of you"; or again, the head to the feet, "I have no need of you."

1 Corinthians 12:21 (NASB)

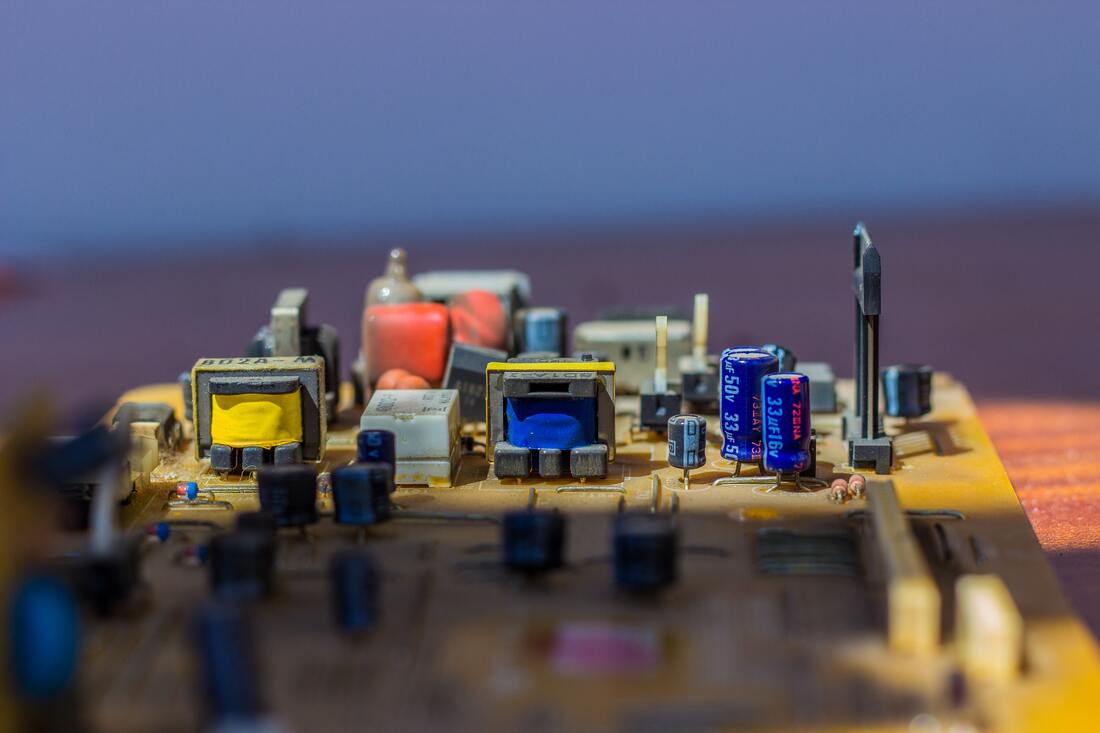

The image that came to my mind as we discussed it last night was one of a circuit board. See, the parts of the circuit work specifically because they're connected. They all do different things and they serve the whole in different ways and maybe even at different times, but they are all part of the same circuit. And being part of the same circuit is not only preferred, it is required. The thing about body analogies (which, admittedly, was probably the best image available to Paul at the time) is that it's easy to note that the eye can continue to work as designed even if the hand has been cut off; but this isn't true of the church, and it isn't true of a circuit. In the case of the hand, the hand suffers complete loss by being separated from the body, and the body suffers the loss of a single function but continues on working in general. In the case of a circuit, breaking the circuit at any point shuts the whole operation down. The pieces are interdependent. It doesn't matter how close an LED is to the power source, if the circuit is broken at a missing transistor twenty connections away, the circuit is broken, and the light will not shine.

The church is not a collection of individuals, each empowered by the Holy Spirit and thus made greater than the sum of its parts when brought together. The church is a circuit, with each part energized by the Holy Spirit because the Holy Spirit is energizing the whole. He does live in us individually, and unlike a circuit component we can learn some in private reading and prayer, but the design for us as Christians and the way we are expected to function is as a community, working together and supporting one another in all that we do. We must prioritize the ways we connect and help keep the circuit working over our private edification if we're ever going to be effective at the mission. My phone will not work properly, will not have any ability to serve its purpose well, if I started taking pieces out of the motherboard. If I expected the components to do their work apart from the whole.

In what ways are we prioritizing ourselves over our communities? In what way can we put the health and mission of the church as higher than our own personal calling, and align our lives to serve in the way we're designed? Are we taking seriously that we are a part of a whole, and have we considered what that means for the way we spend our time, the way we exercise our gifts, the way we relate to one another?

Archives

January 2023

September 2022

August 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

January 2022

January 2021

August 2020

June 2020

February 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

February 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

Categories

All

1 Corinthians

1 John

1 Peter

1 Samuel

1 Thessalonians

1 Timothy

2 Corinthians

2 John

2 Peter

2 Thessalonians

2 Timothy

3 John

Acts

Addiction

Adoption

Allegiance

Apollos

Baptism

Baptist Faith And Message

Baptists

Bitterness

Book Review

Christ

Christian Living

Christian Nonviolence

Church Planting

Colossians

Communion

Community

Conference Recap

Conservative Resurgence

Deuteronomy

Didache

Discipleship

Ecclesiology

Ecumenism

Envy

Ephesians

Eschatology

Evangelism

Failure

False Teachers

Fundamentalist Takeover

Galatians

General Epistles

Genesis

George Herbert

Giving

Gods At War

God The Father

God The Son

Goliath

Gospel Of John

Gospel Of Matthew

Great Tribulation

Heaven

Hebrews

Hell

Heresy

History

Holy Spirit

Idolatry

Image Bearing

Image-bearing

Immigration

Inerrancy

Ireland

James

Jonathan Dymond

Jude

King David

Law

Love

Luke

Malachi

Millennium

Mission

Money

New England

Numbers

Pauline Epistles

Philemon

Philippians

Power

Pride

Psalms

Purity

Race

Rapture

Redemptive History

Rest

Resurrection

Revelation

Romans

Sabbath

Salvation

Sanctification

School

Scripture

Series Introduction

Sermon

Sex

Small Town Summits

Social Justice

Stanley E Porter

Statement Of Faith

Sufficiency

Testimony

The Good Place

Thomas Watson

Tithe

Titus

Trinity

Trust

Victory

Who Is Jesus

Works

Worship

Zechariah

RSS Feed

RSS Feed