|

The reason my blog is called "The Worst Baptist" is because of the reception I have had in many Baptist spaces to some of my views, mostly on matters of application. I disagree broadly with Evangelical trends concerning political matters, I'm still a bit more Charismatic than many Baptists who don't have a background in Pentecostalism (and some that do), and I have an anti-authority streak you could land a plane on. These, and other (often related) matters, put me at odds with my Baptist brethren, and have raised suspicions about my true affiliations more than once. So the name of the blog is kind of a joking acknowledgement of that. I don't actually believe I'm the worst Baptist, I am simply comfortable knowing that there are those who would view me as certainly among the worst of the Baptists. But the fact remains that, regardless of how good or bad I am at being a Baptist, I am a Baptist. And part of the reason I ended up among the Baptists in the first place is that I affirm the Baptist view of baptism. Which doesn't take very long to say, certainly not long enough for its own blog post. But I was asked a little while back by a Lutheran friend to explain the Baptist view of baptism, so I'm going to take this opportunity to do so.

Baptists believe that baptism is done by immersion. That is, if you have not been dunked into the water and then brought back out of it, whatever else happened, you haven't been baptized. Now, this was not always the case; the first Baptists performed baptism the same way everyone else did at the time, by pouring water over the subject. This was something that had to be worked out, but if we're honest, it's one of the simplest aspects of our beliefs about baptism to explain: the word "baptize" most literally means "immerse."  Photo by Joel Mott on Unsplash. Used with permission. Photo by Joel Mott on Unsplash. Used with permission. The English word baptize is just a transliteration of the Greek word βαπτιζω (baptizo), which means to immerse and wash. It is only used in the New Testament to signify a ritual immersion, so it may have taken on a certain connotation in the culture of first century Palestine, but even under these conditions the actual meaning of the word always found its root in immersion. The early church took an existing practice of ceremonial immersion and saw in it a picture of redemption and applied it as such. As far as we are concerned, the Baptist practice of baptism by immersion is little more than a return to this practice. That is not to say there isn't some degree of wiggle room here. Technically speaking, one of the possible meanings for βαπτιζω is washing, and washing doesn't technically always include immersion. Nor does every form of Jewish ceremonial washing include immersion, at least not of the whole person; it is possible that the practice being described in scripture was more like non-immersive methods of ceremonial washing. However, given that it was not the only word used for washing, and that it is primarily used for immersion and has clear ties to βαπτω (bapto), which means to dip, I maintain the historical Baptist position that the scriptures which use the term are most easily read as involving immersion. As will be discussed later, the Didache (the earliest known non-Bible writing of Christian teaching) also discusses baptism. In this instance, it demands immersion (in running water), and allows for the pouring of water over the head of the baptized only in the instance where absolutely no better method can be performed (1). It is not only the wording of scripture then, but also the practice of the early church, that baptism done properly relied on immersion or the closest one could come to immersion. The result of this is that I, as a Baptist, not only insist on practicing baptism by immersion, but cannot accept a baptism delivered by another means. Baptist churches generally have a requirement that a person be baptized in order to be accepted as a member of the church; if someone is joining a Baptist church and points to their being sprinkled as a baby, I and the bulk of Baptists hold that they have not met that requirement and must be baptized. This isn't strictly because of mode, however. It also comes back to whether or not what was administered to them was even theirs to receive.

Baptists believe that baptism should be reserved only for those who have made a confession of faith. As I've discussed before, this is related to our belief that the covenant community only includes those who have been redeemed, that is, those who have saving faith in Christ. Ultimately, what this comes down to is the nature of the new covenant in Christ. You see, it is generally agreed upon by the various denominations within Christianity that baptism is a sign of entry into the covenant community of Christ (some hold it as more than a sign, but none hold it as not at least a sign; that is, they may hold it as a sign and as something greater, but it is always a sign, and as a sign it is always a sign of entry into the community). Therefore, the question of who gets baptized and who doesn't, and when baptism should be applied, ultimately comes down to the question of who is in the covenant community and when they enter it. Baptism should be applied to a person who is entering the covenant community at the time when they enter; defining one category will inherently define the other. The Baptist (and Baptist-adjacent) view is that the covenant community is composed only of those who have been redeemed by the blood of Christ; there are other views which hold a different view of who belongs to the covenant community, and therefore who receives baptism. Now, in my last post I argued for a definition for the church that is incompatible with a view that anyone not yet saved is part of the covenant community, but I want to lean a bit more into how that plays out here. Paul did baptize people into bodies that were not yet churches, see for instance the story of Philippi in Acts 16. Here, Lydia and her household are baptized on their reception of the gospel, and the jailer and his household are baptized on conversion, but the body was still not yet a church when Paul left the city. Which would suggest that the local church and the covenant community are not perfect synonyms, and usually the language used is that baptism is part of entry into the church. But I have used the phrasing 'covenant community' on purpose in the paragraph above; that is, we baptize into the body of Christ, of which the local church is an expression. Essentially, you can have a covenant community where there are believers gathered for the advance of the gospel in service to Christ, but it is not a church until it reaches a certain level of establishment. The definition of 'church' is a refinement of the definition of a 'covenant community,' in which all churches are covenant communities but not all covenant communities are churches. But the fact remains that the covenant community must be composed of those who are actually within the covenant. Astute readers will note that I cited a passage often used to argue for the baptism of infants. The argument essentially goes that, since whole households were baptized, we can reasonably assume children were included, and therefore Paul baptized children. But assumptions cannot guide us here. The fact is that households are not ever guaranteed to have children in them, even in our modern day, and especially then. At the time of writing the Acts accounts, the concept of a household included everyone who participated in the life of the home, which included extended family and servants. Note also that the description of baptizing whole households happens in the context of people who were in certain stations of society. These are people like a rich woman, a jailer who was tasked with significant responsibility, a centurion (encountered by Peter) with a body of servants actively discussed in the text. Their households absolutely did include more than merely themselves and a possible spouse, but there is no reason to believe that this must have included children. There were, in all cases, enough people in the home to use a broad term such as 'household' without the addition of infants. We cannot, therefore, safely assume there were children being baptized in those instances, and the rest of the New Testament offers no support for the baptism of children. Even the statement that "the promise is for you and your children," as is sometimes cited by pedobaptists, is a statement of scope and perpetuity rather than a statement of infants as members of the body, as evidenced by the rest of the statement, "Repent, and each of you be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins; and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. For the promise is for you and your children and for all who are far off, as many as the Lord our God will call to Himself." (Acts 2:38-39, NASB). That is, the promise being tied to baptism here is for those who are brought to Christ, regardless of generation or location. Where the Bible offers no direct support for the baptism of infants, it does consistently address churches as places where the members are assumed to be in Christ. In every letter of the New Testament, the recipients are held to the standard that they have already accepted the gospel of Christ, and at no point is there discussion of people being part of the church but not saved by Christ, unless it is an urging to remove them from the church. Further, the teachings of the early church did not align with the idea of infant baptism. Consider the way baptism is described in the Didache, where baptism happens "after first explaining all these points," that is, the preceding body of the Didache, and the command to "require the candidate to fast one or two days previously"(2). Both elements cited here operate only within an environment where the one being baptized has some ability to receive and respond to instruction. All told, then, the Bible contains no stated baptism of infants and has no knowledge of a definition of the church which includes those not yet saved, and the known practices of the early church required a candidate for baptism to be capable of receiving instruction and following that instruction. "But," one may argue, "what about Jesus' command not to forbid the children from coming to Him?" And to this I would state simply that we don't. We point our children to Christ, we encourage them to rely on Him for salvation and rejoice in Him for His goodness, and we baptize children as soon as they make a confession of faith. The only way to read this behavior as keeping children from Christ is to operate on the understanding that baptism itself carries the power to bring people to Christ.

In every instance of baptism in scripture, it occurs after the person has repented. This should, itself, be sufficient evidence that baptism affirms salvation but does not confer it, except for one statement in the Bible that requires a moment of discussion. This is the statement in 1 Peter 3:21 that "baptism now saves you." Let us begin by looking at the statement in context. For Christ also died for sins once for all, [the] just for [the] unjust, so that He might bring us to God, having been put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the spirit; in which also He went and made proclamation to the spirits [now] in prison, who once were disobedient, when the patience of God kept waiting in the days of Noah, during the construction of the ark, in which a few, that is, eight persons, were brought safely through [the] water. Corresponding to that, baptism now saves you--not the removal of dirt from the flesh, but an appeal to God for a good conscience--through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who is at the right hand of God, having gone into heaven, after angels and authorities and powers had been subjected to Him. |

The Controversy | |

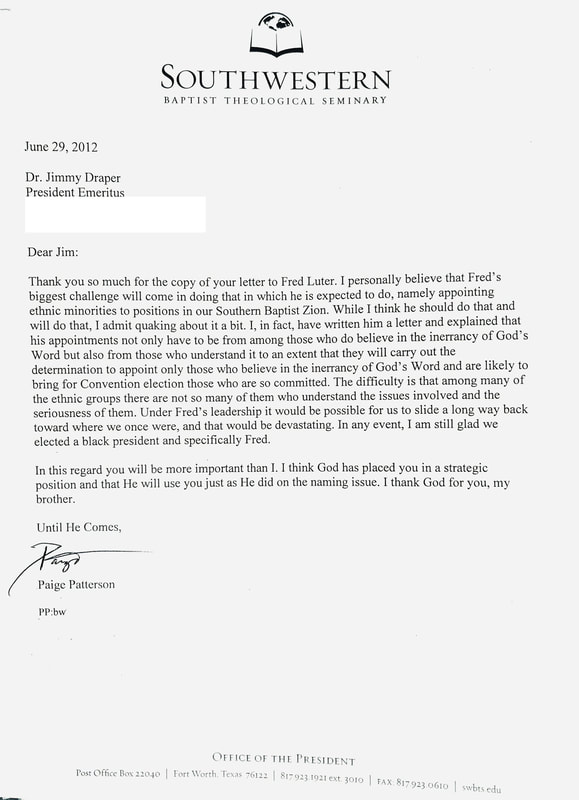

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a number of Christian denominations had to wrestle with the role of scripture in the revelation of truth. The primary camps this usually fell into were those who held that the Bible was fully true in both its concepts and facts (called inerrancy), and those that held it was only fully true in its concepts. The former, for instance, would hold that Jonah literally spent time in the belly of a whale or great fish, while the latter would hold that the lesson taught by Jonah's story was important but the details were probably fictional. The SBC's turn to wrestle with these issues began with commentaries and books published as early as 1961, but kicked into a real fight in 1979. Guided by men including Paige Patterson, Adrian Rogers, and Paul Pressler, the churches which held to inerrancy (which was the vast majority of them) sent messengers to the SBC annual meetings and elected Convention Presidents and entity trustees who also held to inerrancy, thereby slowly shifting the seminaries and ministries of the SBC in a conservative direction. The matter was considered functionally resolved with the publishing of the updated Baptist Faith and Message in 2000. Most of those who opposed inerrancy left the denomination.

During the controversy, nearly everything had to be called into question. People seeking to keep their jobs while opposing the shift were very careful about their wording to suggest that they believed in the truth of scripture while avoiding making any solid statements on the details of scripture. Those who considered themselves liberal or moderate described the conservatives as lusting after power and causing unnecessary division in the denomination just to claim control. Some churches that seem to have actually agreed with the inerrantists ended up opposing them out of a belief that the resurgence or takeover was about a political agenda rather than a doctrinal difference. Those who took the side of the conservatives, which ended up winning the day, were those who saw past careful wording or caricatures to look for the doctrinal root of everything that was being said and done. An entire generation started as children, went to Bible college and/or seminary, and then took posts at Baptist churches and colleges during the controversy. That generation, and the one that was leading the controversy, spent over two decades training to see the world along very specific doctrinal lines and to look for the opposition that wore the masks of allies. This was necessary, the whole fight was necessary in my opinion, because ultimately the cause of inerrancy warranted a defense and this was the defense that needed to arise at that time.

The problem comes when you take combat strategies into a time of peace.

Battle Scars | |

So what does that have to do with the letter, or my earlier post about the Founders Ministry dispute? The short answer is that a generation who views the world in terms of finding hidden enemies will always see enemies hiding among their friends.

The Controversy taught that generation that any difference in belief or practice is a signpost indicating a deeper attack on scripture. Those who raise questions about how the SBC handles things are trying to undermine the work of the Controversy Generation in reestablishing the authority of scripture. Those who come from a different perspective and therefore see a different application for the truths of scripture are substituting secular ideologies for the gospel. Every doctrinal or practical difference that can be associated with a different treatment of scripture must be viewed as an attack on inerrancy.

And this is what Patterson was expressing in his letter. Whether conscious or not, the fear was that minority pastors, who have a tendency to view the SBC and the Bible in light of a different set of life experiences than white pastors, are in fact interpreting the Bible as subject to those experiences. That the interpretation of scripture does not begin with the claim that the Bible is factually true and the ultimate source of truth, but rather that the truth claims of scripture can and should be measured against a different standard. This is the same complaint of Founders Ministries, and the same fear that pushes against reform in the treatment of abuse victims, and the same understanding that led John MacArthur to misrepresent the actions voted on by the SBC over this past summer, and the same standard that demanded Kanye West to display a certain level of doctrinal maturity before his conversion can be seen as valid. It is present in churches, ministries, schools, conferences, and online spaces. And the thought process can be shown by example.

Liberation Theology is a school of thought largely held in black churches and present among other minorities that sees a certain relationship between the slavery to sin and the slavery of their ancestors (and/or ongoing issues and oppression they face), and therefore read the liberation from sin and its effects as a particularly notable promise in their lives. While individual views may vary, the core idea of the theology is that freedom in Christ is an important aspect of the gospel that has specific and unique application in their lives. Patterson's letter does not cite the existence of this framework as part of his concern, it is merely being used as an example. Detractors of liberation theology, however, view the emphasis on freedom from sin as a replacement for penal substitutionary atonement (the belief that the primary purpose of the death of Christ is to take on the weight of our sin on our behalf) and, as such, a false gospel. And, of course, a false gospel must come from a different read of scripture; and a different read of scripture, to the Controversy Generation, is probably a sign that inerrancy is being denied. Therefore, by this logic, allowing liberation theology to have a place in the SBC is a challenge to inerrancy and a reversal of the Controversy's achievements. That some opponents also believe the claims of ongoing oppression are false is relevant when it comes up, but on a doctrinal level this is the actual issue.

But this mindset, while a very good tool during the fight for inerrancy, causes more problems than it solves when it is applied to differences that do not come from the issue of inerrancy. Black people who hold to liberation theology, by and large, are not wrestling with what the gospel actually is or how the Bible defines it; they are wrestling with what that gospel looks like as it interacts with their lives and communities. Disputes about the nature of the manifested Kingdom of God do not generally arise from a dismissal of the authority of scripture, but from different attempts to piece together the authoritative clues that scripture contains. Allowing for the use of secular tools designed to help victims of abuse is rarely an attempt to reject the Spirit speaking through scripture as the primary means of healing, but an attempt to understand what specific needs a victim may have and therefore what parts of scripture or aspects of the gospel will best speak to those needs, and how to apply them in a healthy manner. But when these issues are handled with the mindset instilled in the Controversy Generation, the natural response is to oppose good things being handled by righteous servants of God out of fear that anything different is an attack in disguise. This pushes people away who are actually allies, causes continued pain in people who come to the church seeking healing and find only rejection, and damages our witness to those watching how we shoot at each other over every minor dispute.

Brothers, this cannot stand. I have said before that I support the work carried out by inerrantists during the Controversy, and I stand by that; I also believe it is necessary to see the impact the Controversy has had on the people who fought in it, and the ways their scars can cause unnecessary division now. We have had to fight for inerrancy before, and it is possible we shall have to again; but the question right now is what a church that holds to inerrancy will look like in a hurting world coming to grips with a host of problems that are being brought into the light. If we will not fight the battles that really exist because we are too focused on those fought decades ago, we will face a much greater loss than the roughly 1,900 churches who left during the Controversy. It is time to lay these weapons down, pick up the scriptures we fought so hard for, and begin exploring what it looks like to live them out today.

A Survey of Causes and Consequences, with Particular Focus on the Role of Baptists Throughout

If Irish Baptists are readily ignored in Ireland, they are even more so for those outside of the island. Few books of Baptist history discuss Ireland, and those that do generally give it very little space. In its treatment of Greater Britain, H. C. Vedder’s Short History of the Baptists gives one paragraph to Ireland and two to Alexander Carson, a prominent leader in Irish Baptist life. In summarizing the paragraph on Ireland, Vedder simply states that “comment is almost needless. Baptist churches have ever found Ireland an uncongenial soil”[2]. This is hardly surprising, given the nature of their arrival to the island.

In fact, the two most influential events in Irish Baptist history are arguably the conquest by Oliver Cromwell’s army and the Ulster Revival of 1859, and Baptists themselves, while reasonably associated with both, played very little public role in either. The concern of this post will be the latter, but it cannot be fully divorced from the former. The context of the Ulster Revival can be traced through three sources: the general tone of Baptist life in Ireland as established by Baptist arrival and initial struggles, the Prayer Meeting Revival in America of 1857-1858, and the immediate environment in which the Ulster Revival occurred. With this understanding in place, consideration can be given to the revival itself and its results, which are still felt today.

Early Irish Baptists

John Owen, possibly by John Greenhill, c. 1668. Via Wikimedia Commons. | Vedder notes that “There is no reason to suppose that the church antedates the conquest of Ireland by Cromwell in 1649, and in fact our earliest knowledge of such a church is 1653” [3]. Baptists certainly came over with Cromwell’s army, with John Owen preaching to the troops in England before their departure and then travelling to Ireland with them. Cromwell and his associates would paint much of what they did in Ireland as a judgment for atrocities they believed to have occurred in the northern region of Ireland, Ulster, less than a decade earlier. Owen’s own sermon urged the soldiers “to avenge the deaths of Ulster Protestants that had occurred during the rising of 1641” [4]. Cromwell and his army established a name for themselves by a great massacre in Drogheda, which Cromwell |

Owen did not remain in Ireland, but “when [he] returned from Ireland, pleading for missionaries to be sent to the island, Patient was chosen by Parliament as one of six ministers to be sent to Dublin” [6]. Thomas Patient had already served under William Kiffen in London and signed the London Confession of 1644. Patient helped form the Irish Baptist church in Waterford, one of very few from that period still operating today, before being given the preaching position at Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin. While there, “he was responsible for erecting the first Baptist Meeting House in Ireland, in Swift’s Alley, Dublin” [7]. This is the church Vedder refers to as beginning in 1653.

The Baptists in Ireland had been strongly associated with Cromwell’s army, and Baptist churches on the island were still largely composed of soldiers and their families. When Charles II restored the throne in 1660, much of that army returned to England, leaving their churches largely empty. The remaining Baptists were caught in a vice between the crown and the Irish, both hating them for affiliation with Cromwell. In fact, “the Baptist cause is described as having ‘lingered rather than lived’” through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries [8].

A Revival of Prayer

A week later, twenty attended the prayer meeting, and attendance was nearing forty when the third meeting came together on October 7. With excitement building, it was decided that the meetings would occur every day, beginning immediately. As the building began to fill, other nearby churches and open spaces opened their doors for the growing prayer meeting movement. As of February 1858, “not less than one hundred and fifty meetings for prayer in this city and Brooklyn were held daily,” and that same month saw the first related prayer meetings begin in Philadelphia [13].

Almost immediately after, other meetings sprang up in cities as far abroad as Boston, New Orleans, St. Louis, and Chicago. Accounts began to arise about boats travelling to New York being swept up in the activity before making land. In Samuel Prime’s 1859 account of the prayer meetings, an entire chapter is devoted to the work done through Mariner’s Church in Manhattan to minister to sailors that carried word of their conversion overseas, and “ from there it spread to Canada, the British Isles, Scandinavia, parts of modern Germany, Geneva and other parts of Europe, as well as settler communities in Australia, southern Africa and India” [14].

An Island in Crisis

An Irish Peasant Family Discovering the Blight of their Store by Daniel MacDonald, c. 1847, via Wikimedia Commons.

An Irish Peasant Family Discovering the Blight of their Store by Daniel MacDonald, c. 1847, via Wikimedia Commons. The Baptists in Ireland fared little better, if at all, than the Catholic majority during the potato blight that struck in 1842. The population was devastated, to the point that

The Baptist churches of Ireland worked hard to provide for the needs of their neighbors, but between their own suffering and the loss of large numbers of adherents, they were quickly falling into a deficit. As the blight ended, more troubles struck Ireland, these coming in the form of higher taxes owed to Britain. William Ewart Gladstone, then chancellor of the exchequer in England, explained a new fiscal policy for Ireland in 1853 that included a higher spirit duty and an income tax that was expected to be temporary and only affect the wealthy. Instead, “the net result was that Irish taxation rose by some £2,000,000 a year, at a time when the only hope for the national economy was the investment of more private capital” [19]. Everyone in Ireland suffered to some degree under the plan.

Meanwhile, Ulster was in a war over the political influence of religion. The Roman Catholic Church was dealing with an internal struggle over the concept of ultramontanism, a strong system of belief in the power of the Catholic hierarchy. Ultimately, the ultramontanists would win that battle with acceptance of the doctrine of papal infallibility in 1870. The ultramontanist movement was gaining strength in Catholic Ireland and the Presbyterians, fearful of losing political power to the Roman pontiff, “were appalled by government concessions to popery and in 1854 the General Assembly formed a Committee on Popery to monitor the progress of Catholicism in public life and arrange lectures on anti-Catholic themes” [20].

The Presbyterians themselves were recovering from an internal battle, where

The new movement the Presbyterians hoped for would be sober and respectable. It would produce great fruit with little fuss. What they saw happening in America in 1858 sounded like an answer to their very specific prayer; however, “revivals seldom conform to the sober desires of religious professionals. The revival of 1859 was no different and unleashed forces that challenged the status quo and caused considerable unease and controversy” [22].

The Ulster Revival of 1859

Conversions began to occur at Tannybrake and Kells, and one soul saved was a man named Samuel Campbell. Campbell returned home to Ahoghill, where he led his mother and siblings to the Lord. The last of his family to follow Campbell to faith was his brother, who in March 1859 was so stricken with the weight of his sin that he nearly collapsed upon hearing the gospel, and spent many days in dire spirits until he finally came to Christ. This would be considered the first of many manifestations that would accompany the revival that was beginning.

As conversions were starting to draw attention in Connor and Ahoghill, word reached Ireland of the work happening in America. Inspired by the Prayer Meeting Revival, R. H. Carson, son of Alexander Carson and pastor of Tobermore Baptist church, decided on “the formation of a prayer meeting on a Friday evening and this proved to be a fruitful meeting, as a fortnight after its commencement, there were conversions. From March 1859 to March 1860, ninety-two souls were added to the church” [26]. This merged with the revival sparked in Connor as, by this time, “the Heavenly Fire was leaping in all directions through Antrim, Down, Derry, Tyrone, and indeed throughout all Ulster. From Ahoghill the revival spread until, in May 1859, it began to manifest itself in Ballymena” [27].

Revival Controversy

Opponents to the Revival saw a vastly different story unfolding. Their concern largely focused on stories about manifestations that “occurred in a variety of geographical locations and took different forms including stigmata, ‘convulsions, cries, uncontrollable weeping or trembling, temporary blindness or deafness, trances, dreams and visions’, though prostrations were the most common” [32]. These are generally considered to have been relatively rare occurrences that were exaggerated by the press, but they were undeniably a factor in the Ulster Revival despite having no presence in America or the initial waves in Connor. This concern was raised during a June 1859 meeting, in which “the Presbytery of Belfast was positive towards the revival but wary of the manifestations. Professor J. G. Murphy expressed his disapproval and stated his preference for ‘the silent workings of the spirit of God, as likely to be more lasting’. Gibson likewise stated that he ‘had no sympathy with those extravagances’ and recommended a cautious approach” [33].

William McIlwaine, in studying the event and Presbyterian history, came to the conclusion that the manifestations and chaotic nature of some conversions held more in common with the Six Mile River Revival than previous Presbyterians had claimed. He and Isaac Nelson were also concerned about American revivalism in general, and wrote extensively on the subject in Ulster papers. Their major point of concern was that “the revivalist religion of the American Churches led to moral prevarication that permitted slaveholders to remain church members” [34]. They held that, if revival was not sufficient to make the church address and mourn its nation’s most glaring sin, then it was not changing hearts. Ultimately, however, McIlwaine and Nelson remained in the minority, and the effects of the Revival went on without them.

Consequences of the Revival

The Revival also had very little impact on the state of the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland. While some accounts mentioned Catholics converting during the Revival, “it is clear that the revival made little impact upon the Catholic population in Ulster, none at all in southern Ireland and there was little or no effort made by the Protestant Churches to evangelise Catholics” [37]. The Presbyterian church did not gain the political power over the Catholic church that it had been seeking, but did solidify its position as part of an Ulster-Scots identity. That identity would go on to fuel unionist rhetoric when the rest of Ireland sought independence from England, and heavily influenced the politics of the new Northern Ireland when the island was eventually split in two.

The wave of revival did not stop in Ulster. Scotland and Wales saw revivals in that same period, and

The success of the Revival was largely measured by the experiences of those in it, with doctrine becoming a secondary issue. Supporters of the Revival pointed to individual piety, a clear moment of conversion, and social factors such as temperance as evidence of the work of God. The concern about personal piety and experience started a shift in Presbyterian thought, where “theologians increasingly saw religious experience as the essence of Christian faith and placed it at the centre of their inquiries, characterising the Bible as a record of the developing spiritual experience of humanity rather than as a manual of doctrine” [40]. The battles fought within Presbyterianism at the beginning of the nineteenth century, which solidified a more concrete conservative nature to the denomination, came under a new assault as “the use of the language of experience...allowed some opinion-formers within the Presbyterian Church to adopt higher criticism and to be accused of promulgating so-called modernist theology. Those sympathetic to modernism could separate the text of Scripture from the spiritual experience to which it gave witness while the laity could retain their pietistic spirituality” [41].

Baptists did not seem to fall into this same error at the time, but once the idea was in place, it would arise again; the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy that split almost every major Protestant denomination in the early twentieth century can be largely traced back to the debates within Presbyterianism in the years after 1859. Both Northern Baptists and the Southern Baptist Convention would end up having this same fight in the twentieth century, with the fundamentalists breaking away in the north to form the Conservative Baptists of America while modernists were driven out of the Southern Baptist Convention.

The Irish had been increasing their attempts to control their own land in the wake of the potato blight, when it was shown (in the most charitable wording possible) that the British concern for the island was insufficient to the needs of its people. Having entered the revival period with little outside help and growing problems, the Irish Baptists came through the 1860s with a growing body and a renewed vigor for the work ahead. It was enough of a head start that, with 29 churches, “the Baptist Union of Ireland was formed in 1895 and links with the Baptist Union of Great Britain were severed” [42]. While political independence would happen for the Irish later, the Baptists of the island had achieved some measure of religious self-determination.

Conclusion

Baptists played a significant role in the Ulster Revival of 1859 and benefited greatly from it, even if they are hidden in the shadow of the Presbyterian work. What had been a struggling body of believers barely holding on to its place in Ireland had come to stand on its own feet. The place they carved out for themselves is still growing, although slowly.

One woman presenting Christ to a young man in County Antrim, and one man sitting down to pray with the doors open for others to join in New York City, were used by God to change the character of Christianity in Ulster and the greater United Kingdom. This seed was not too small to see a revival--perhaps the Baptist churches of Ireland are not too small a seed to see an even greater movement of God today.

Footnotes

At the core of this issue is the question of what the church is. If the church is basically a regional expression, a sort of divine government over a parcel of land, then it should make sense that people be incorporated into it based on their place of birth, as citizens of both a physical and a spiritual nation. However, there is no trace of this idea in scripture. If Paul could say to the church in Corinth, “now you are Christ's body, and individually members of it,” then the church must be defined by its relationship to Christ (1 Cor 12:27 NASB). That is, in order for the church to be Christ’s body, the church must be in Christ - and no one is in Christ who has not been redeemed by him. If the church are specifically those who have become “dead to sin, but alive to God in Christ Jesus,” then there can be no one in the church who are not yet dead to sin, and only those who have been made alive in Christ can be members of it (Rom 6:11 NASB).

So the Baptist holds that the defining trait of the church is that it is the body of Christ, or more specifically, the gathering of those who are in Christ into one body. This doctrine naturally flows into all others by which the Baptist can be recognized. If the body of those in Christ gathered is the body of Christ, then the local church is able to stand as the body of Christ. The local church is independent, not reliant on a larger body whether religious or secular for authority to operate as Christ’s body, and has for itself Christ as its head (cf. Col 1:18). This frees the local church not only from the structures of a larger religious body but also from the dictates of any mortal government. The local church is an expression of the fullness of the body of Christ just as Christ, though finite in His body, was able to express the fullness of the infinite God while walking the Earth. This enables the local church to carry out the full mission of Christ’s body in the world without borrowing authority from a larger structure, including ordaining, releasing, and holding accountable their own leadership; while leaving the local church free to partner with other local churches as equals.

If the church is composed of those who are in Christ, then the mark of entry into the body must be given only to those who are in Christ. The idea that baptism is the mark of entrance into the church is not specific to Baptists - most, if not all, denominations would agree with that claim. The different ideas on when baptism should be applied are based not on the function of baptism, but are fundamentally built on differing ideas of what the church is and therefore who receives entry. As stated above, a view of the church that equates entry with physical citizenship must baptize immediately, as the child is understood to be in the church at the time of birth. A belief that the church is the gathering of those in Christ’s body, however, demands that baptism be withheld until a person is actually in Christ’s body.

This also informs the difference between those bodies who believe that baptism has any ability to save or impute grace onto the baptized, and the Baptist who believes it to be only a sign. If baptism is applied after one is already in Christ, then the baptism itself cannot hold any power to place one into the body. It cannot change one’s nature into that which it already is. In fact, all ordinances of the church must be symbolic. If a person can only be in the church by already being in Christ and redeemed by Him, then no practice of those already in the church will have the power to bring people into it. Baptism cannot redeem because it is applied to the already redeemed, and the same goes for the taking of bread and wine in communion. The body and blood of Christ have no need to be physically present in the bread and wine because the body gathered is the physical manifestation of the body of Christ already. Christ is present in a special way whenever and wherever His people are gathered, they do not need to invoke Him into presence through another medium (cf. Matt 18:20).

When one is asked to define the distinction Baptists and Baptist-like bodies have with all other groups of Christians, the answer must begin with the doctrine of the believer’s church. All other things that define the Baptists as a specific and unique movement are born from this doctrine. However, the need to grasp this distinction goes beyond simply defining Baptists to those who are not Baptists. Keeping this understanding in mind also enables the local church to hold itself, its members, and its leadership accountable to its effects. The local church, as the body of Christ, must be working on the mission Christ has given it. The church must be vigilant that it recognizes those who are in Christ and refrains from giving undue authority to those who are not, whether they are attending church services or sitting in positions of political power. In order to faithfully carry out the identity Baptists have, the individual Baptist must know what that identity is- and it begins by grasping the doctrine of the believer’s church.

Archives

January 2023

September 2022

August 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

January 2022

January 2021

August 2020

June 2020

February 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

February 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

Categories

All

1 Corinthians

1 John

1 Peter

1 Samuel

1 Thessalonians

1 Timothy

2 Corinthians

2 John

2 Peter

2 Thessalonians

2 Timothy

3 John

Acts

Addiction

Adoption

Allegiance

Apollos

Baptism

Baptist Faith And Message

Baptists

Bitterness

Book Review

Christ

Christian Living

Christian Nonviolence

Church Planting

Colossians

Communion

Community

Conference Recap

Conservative Resurgence

Deuteronomy

Didache

Discipleship

Ecclesiology

Ecumenism

Envy

Ephesians

Eschatology

Evangelism

Failure

False Teachers

Fundamentalist Takeover

Galatians

General Epistles

Genesis

George Herbert

Giving

Gods At War

God The Father

God The Son

Goliath

Gospel Of John

Gospel Of Matthew

Great Tribulation

Heaven

Hebrews

Hell

Heresy

History

Holy Spirit

Idolatry

Image Bearing

Image-bearing

Immigration

Inerrancy

Ireland

James

Jonathan Dymond

Jude

King David

Law

Love

Luke

Malachi

Millennium

Mission

Money

New England

Numbers

Pauline Epistles

Philemon

Philippians

Power

Pride

Psalms

Purity

Race

Rapture

Redemptive History

Rest

Resurrection

Revelation

Romans

Sabbath

Salvation

Sanctification

School

Scripture

Series Introduction

Sermon

Sex

Small Town Summits

Social Justice

Stanley E Porter

Statement Of Faith

Sufficiency

Testimony

The Good Place

Thomas Watson

Tithe

Titus

Trinity

Trust

Victory

Who Is Jesus

Works

Worship

Zechariah

RSS Feed

RSS Feed